Early in my career, I got to be part of something extraordinary. I was one of the first 20 or so people on the Xbox team. The video game industry typically worked in 4-5 year cycles — giving Sony, Nintendo, and Sega enough time to research & develop the next generation of video game console hardware and content. Microsoft gave itself 18 months to launch Xbox. Those 18 months were a time of incredible speed, creativity, and industriousness. They exposed teams that worked well — and teams that struggled. In those months, I learned a simple tool to organize high performance teams that I’ve used ever since.

In 2000, Microsoft believed the next generation of consoles could tap into the tidal wave of the Internet to deliver a completely new type of online, multiplayer entertainment. And Microsoft believed that it was better positioned than Sony or Nintendo to bring the hockey stick trends of the Internet and video games together.

I was the producer on a title that was pushing the envelope of what could be done by bringing the fast-paced kinetics of action games into the social experience of a massively multiplayer game. In today’s world where millions of people play Fornite everyday, that idea doesn’t seem so innovative. In those days, it was ambitious work.

Art & Design are incredibly important factors in whether or not a game is entertaining. But, our art team wasn’t doing so well. Many people felt the problem was the Art Director. They said he was disorganized and inattentive to the team. He had to go. Other people saw things very differently. They thought he was creative, visionary, and a big part of the reason the game got funding in the first place. He was indispensable to the success of the product.

It turns out both groups of people were right. The problem wasn’t the Art Director — it was the fact that different people had very different expectations of his role. And it turns out we can solve this with a simple tool.

What does a tech team or company need to do? Just three things: Innovate. Manage. Produce. Problems arise because we tend to organize teams by function or product, not by this simple and essential set of three roles.

What does a team or company need to do?

Just three things: Innovate. Manage. Produce.

Let’s look at our Art Director who was simultaneously brilliant and incompetent. As an innovator, he shined. He oozed creativity. The worlds and characters he dreamt up were astonishing in their originality and detail. As a manager, he was dismal. He was alternately locked in a room dreaming up ideas or frantically shouting orders to turn those ideas into reality.

The Art Director role is vague. Is an Art Director an innovator? The visionary that charts the path forward? Or is an Art Director a manager? The leader that rallies the team to do its best work? Often, the unstated expectation is that a good Art Director is both. Some people are equally great at both, but many people spike in certain areas. Is it fair to them or the team to squander their strengths in hopes of addressing their weaknesses?

In this case, the solution was to reframe the role into two jobs. We moved the Art Director into a Creative Director role focused on defining the artistic and conceptual vision of the game, and we hired a strong leader as an Art Director to lead the team and execute the vision.

In the tech industry, engineering leadership roles often get conflated in the same way. Engineering leaders are often expected to be both tech visionary and skilled team manager. Some companies have recognized the challenge in this expectation and setup distinct roles: the CTO as innovator/tech visionary and the VP of Engineering as team leader.

We need this same clarity in other parts of the business, and we can start with a simple exercise which I call IMP (Innovate-Manage-Produce) analysis. Consider your team and what it will take to succeed. Answer the question:

How much time should we be spending on innovation, management, and production?

Quickly jot down the percentage of effort you need each area:

- Innovation (i.e, defining where your team goes next)

- Management (i.e., enabling your team to deliver to its maximum potential)

- Production (i.e., executing flawlessly against your team’s vision and strategy)

For certain teams, it may makes sense to break this down by function (design vs. marketing vs. engineering) or business area. Now, list out everyone on your team and estimate the percentage of time they are actually spending today on each role.

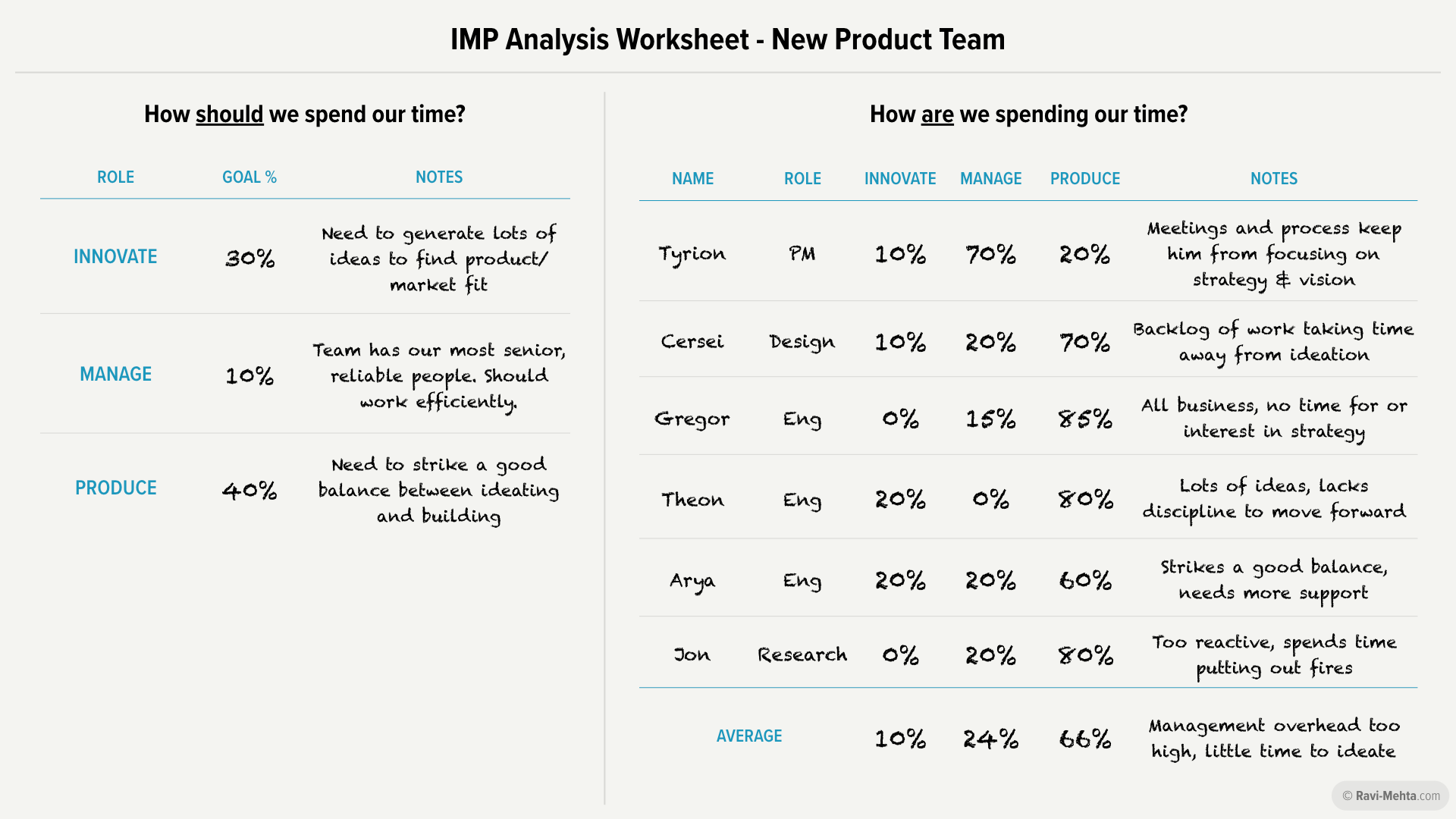

For a two pizza team of 6 that is trying to find product-market fit, the analysis might look like:

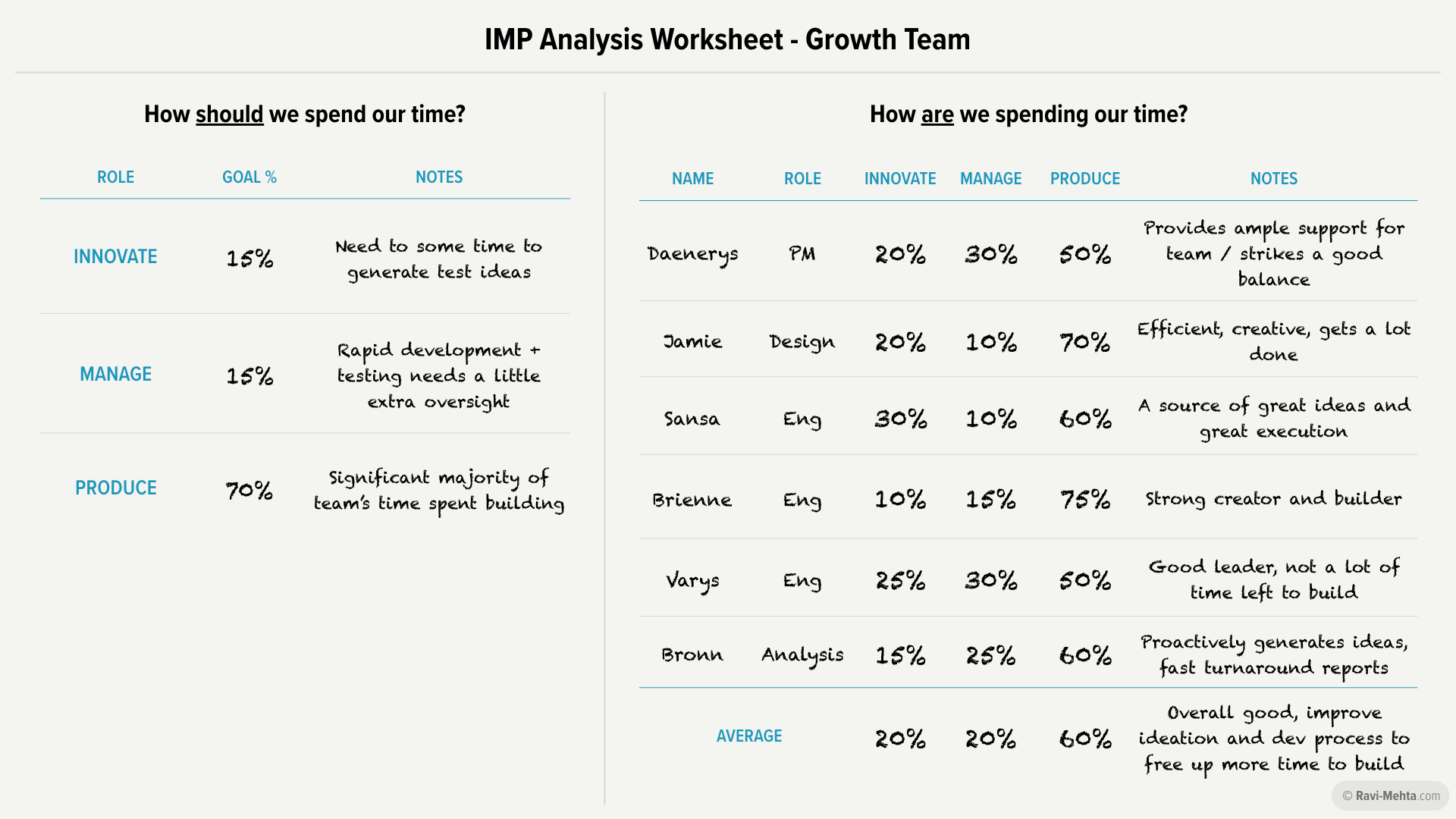

This allocation should look different for a growth team that is rapidly executing on a set of known levers:

The numbers will be rough, but the gap between expectation and reality will be helpful in identifying the specific cause of a team problem that has been hard to put a finger on.

These are some common problems you can identify with this tool:

- Misalignment about whether a leader should be spending time innovating or managing. Leaders often fall into one of two camps: vision-oriented leaders vs. execution-oriented leaders. As with our Art Director example, teams struggle when leaders are expected to do one thing, but are doing something else.

- Misalignment between a person’s strengths and the expectations of their role. Too often, companies expect people to conform to their role, rather than shaping roles to conform to their people. High performance teams adapt to tap into the strengths of every team member.

- New managers spending too much time producing, and not enough time managing. As a person gets more senior, their ratio of time spent innovating, managing, and producing must change. Many new managers hold on to old habits. This reduces their time available to support their team and often results in micromanagement.

- High producing teams mistaking motion for progress. Teams get a lot of credit for getting things done — strong execution is a leading indicator for strong impact. But, this can drive a team to spend all of their time doing and not enough of their time innovating. As a result, teams end up delivering a high volume of output but not high quality outcomes.

- Innovative teams spending too little time delivering outcomes. Innovative teams can suffer the opposite fate. New ideas are energizing. Some teams become enamored with the creative process and resist making the decisions necessary to test their ideas. Creativity without execution is like rocket fuel without a rocket.

Every one knows when they are on a team that is struggling, and you know when you’re in a role that just doesn’t feel right. But, it can be hard to put your finger on the problem. IMP analysis can help. By taking a few moments to make the distinction between innovating, managing, and producing, you can uncover the misaligned expectations and skills that are holding you or your team back.

In a future article, I’ll dive into what the three roles (innovating, managing, and producing) look like for the major functions in a tech company: engineering, product, design, analytics, user research, and marketing. Subscribe below to stay up to date with new tools that will help you scale your product and your people.