At some point in our careers, most of us get the same feedback — to continue growing we must become “more strategic”.

I remember the first time I got that feedback. I was a PM in Microsoft’s gaming group. I had mixed feelings walking out of my boss’s office. I was both excited and anxious. It felt as if the door to the next chapter in my career was opening, but I really had no idea what it meant to be more strategic and how I was going to get there.

I had in my mind that strategy was some big, amorphous topic that requires years of experience, lots of frameworks, and a rare, natural gift.

Over time, I came to a very different understanding of strategy. The people who are strong strategic thinkers aren't necessarily pulling from some encyclopedic playbook. They haven't memorized Sun Tzu’s The Art of War or spent years at McKinsey.

Instead, the best strategic thinkers understand the future outcomes that they're working towards and make decisions that have the highest likelihood of achieving those outcomes. In other words, the best strategic thinkers predict the future based on what they know today.

🔮 The best strategic thinkers predict the future based on what they know today, and make decisions based on that prediction.

Major key alert!

Of course, the idea of trying to predict what’s going to happen can feel daunting. And the truth is, leaders at all levels feel this way.

You and the CEO of a Fortune 500 company have something important in common.

You are both held accountable for predicting the future. The public company CEO needs to give quarterly guidance and succeeds by hitting those goals regardless of all the external factors involved. Similarly, your company, your manager, and your team are looking to you to set and achieve important goals.

One of the best ways to make yourself successful within an organization is to understand that leaders are in the position of predicting the future — of setting goals now and achieving them tomorrow. If you can help them by taking the same responsibility for your area, then you’ve put your career on the fast track.

🔑 Leaders turn to teammates who reliably set and achieve important goals — even when the future is uncertain.

Decisions are the basic building block of strategy

The future unfolds based on the decisions that we make today. Good decisions create valuable outcomes in the future, and bad decisions lead to unnecessary risk. So, we can think of decisions as the basic building block of strategy.

This is why strategic thinking is so important for product work. We're always making decisions — some short-term like “What should this button say?” and others that can have impact for months or years to come such as “What should our OKRs be?”, “What should we prioritize for the roadmap?”, and “What principles underpin our product?”.

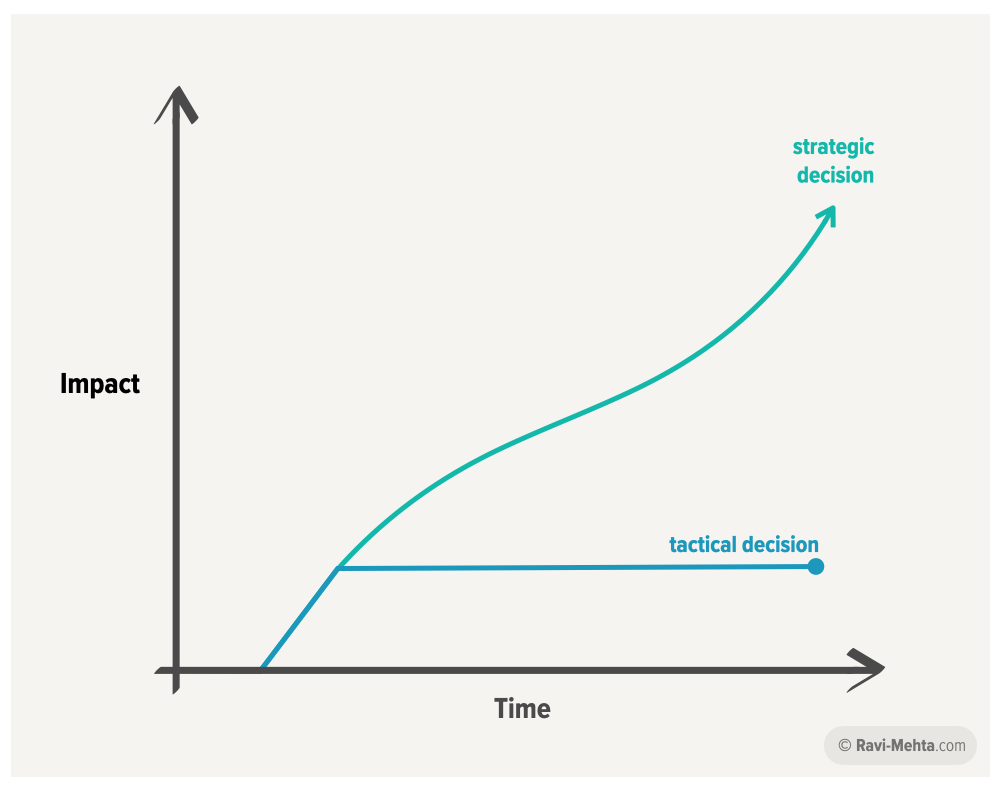

We can make those decisions tactically by thinking only about the immediate moment, or we can think about each decision strategically — a step towards unlocking a valuable sequence of future options, outcomes, and opportunities.

What makes a “good” decision?

Strategic thinking helps us make good decisions. But what exactly is a good decision?

A good decision is not necessarily a “right” decision — that is, a decision that has a successful outcome. We’re predicting the future, and we can’t ever know for certain whether we’ll be right. Every decision involves risk — and sometimes more risk means more opportunity for upside. So a good decision is one that strikes the right balance of risk and reward.

Indecision → Decision

A good decision starts by being clear and specific about the challenge at hand, and the decision that must be made to overcome that challenge. But, this first step is often the hardest. Indecision is like quicksand and can easily lead to feeling stuck or overwhelmed.

In the next section, we will go through a system that can help you map out the future. To make the most of this system, consider a decision you need to make. That way, you can begin to put this tool into practice — and free yourself from the trappings of indecision.

What challenge is top of mind and what decision do you need to make as a next step?

Your Decision Making Time Machine™️

Predicting the future can feel like a hopeless task. There are infinite possibilities… maybe even more with all the multiverses that keep popping up.

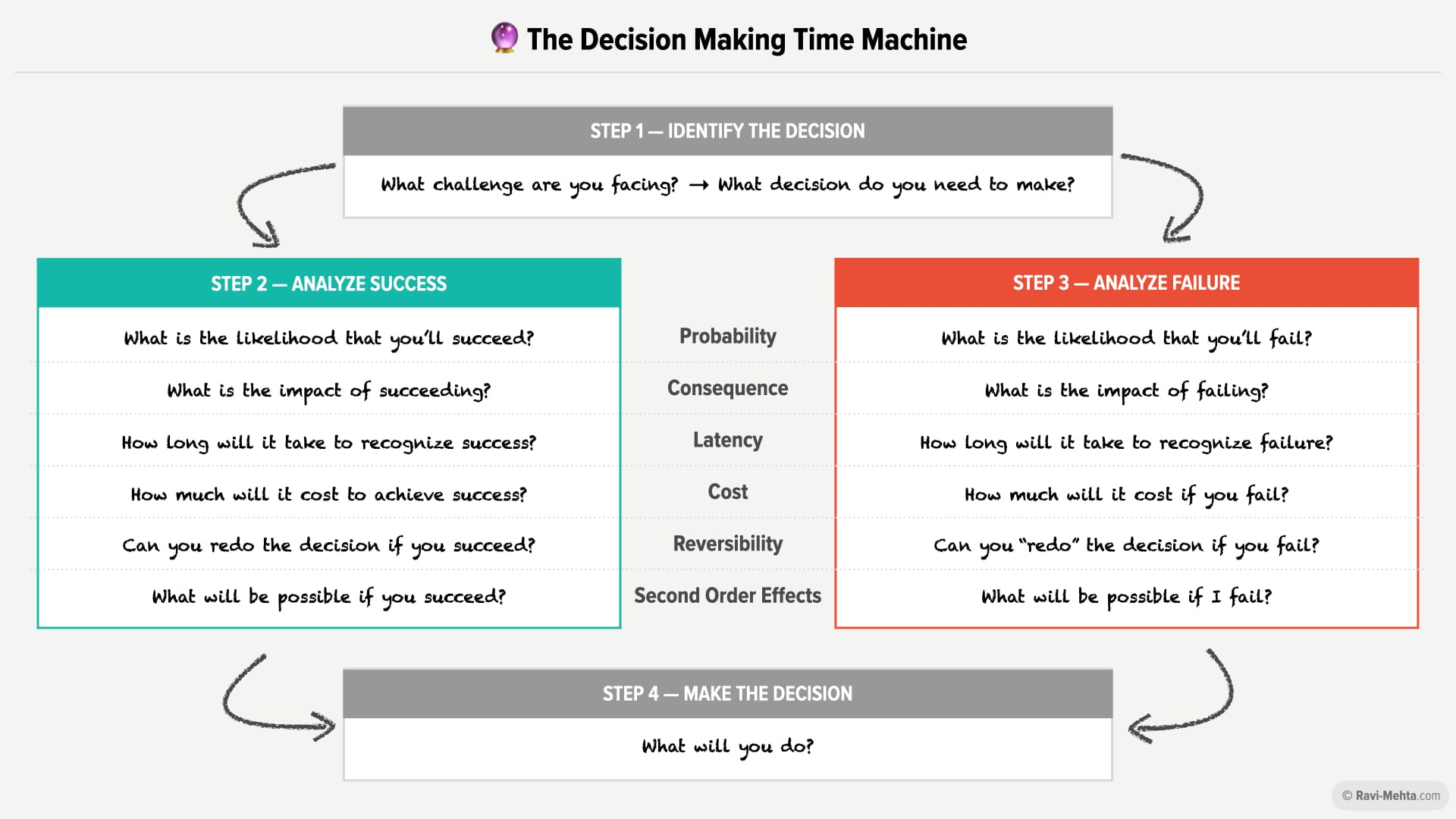

We can make dramatically better decisions by taking a four step approach — and you’ve already started the first step.

- Identify the challenge you are facing and the decision you need to make

- Analyze what a success looks like using the powerful set of decision factors discussed below

- Use those same decision factors to analyze the failure case

- Now, make the decision — you’ll likely be surprised at how easy it is to make a confident decision now that you’ve envisioned how it might play out. This final decision could be to move forward, revise your approach, or forego the decision entirely.

Let’s take a closer look at how this machine works.

Success and failure, sitting in a tree…

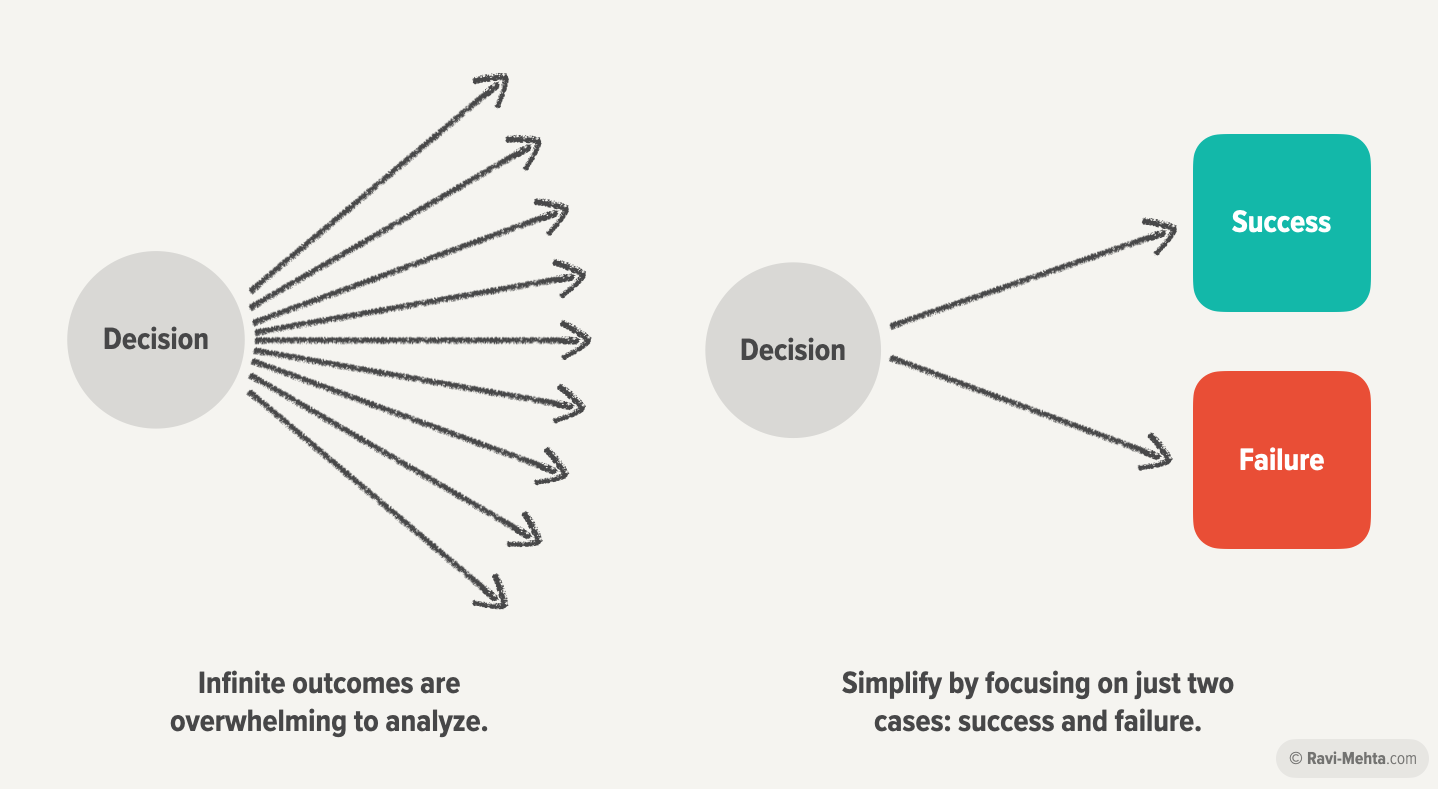

Once we’ve identified our decision, we need to think about how that decision will unfold. Instead of imagining all the things that might happen, define just two outcomes: success and failure. A simple outcome tree helps us think about the future in concrete terms.

For example, imagine you’re making the decision to start a company. Of course, many things might happen from going bankrupt to becoming a billionaire. But, realistically, what is the success case and the failure case?

A freelancer or bootstrapper may define success as replacing their salary, another founder may be focused on a venture-scale exit. So, the definition of success varies significantly from person to person. Similarly, it’s important for each person to define what failure looks like before making a decision. Our entrepreneur likely won’t go bankrupt, but they may be out of a job and have exhausted some savings. Importantly, failure isn’t all negative — founders gain valuable experience even if their venture doesn’t succeed.

Already, we can see the future more clearly by simplifying the outcomes.

As we walk through the success and failure scenarios, there are a series of factors to assess. And it’s very important that we assess them independently for the success case and the failure case — because the answers are NOT mirror images.

This bears repeating. The most common flaw in strategic thinking is to assume that success and failure are equal and opposite. Our brains our lazy so we like to infer one answer from another.

For example, we may inadvertently assume that the chances of success and failure are roughly 50/50. This is rarely the case and gets exacerbated by the fact that people have a very hard time estimating probabilities.

We may also think that risks and rewards are roughly equal. Again, this is rarely the case and fraught with cognitive biases. It’s the reason people lose billions at the casino every year.

So, strategic decision-making requires us to independently assess the success case and the failure case of every decision. Only then can we make a sound strategic decision.

Decision factors

Now we’re ready to start predicting the future! We can do this be looking at six factors that drive how a decision may unfold:

- Probability - What is the likelihood of succeeding or failing?

- Consequence - What is the impact of succeeding or failing?

- Latency - How long will it take to succeed or fail?

- Cost - What are the costs of succeeding or failing?

- Reversibility - Can we “redo” the decision in the future?

- Second-Order Effects - What is now possible as a result of success or failure?

Probability & Consequence

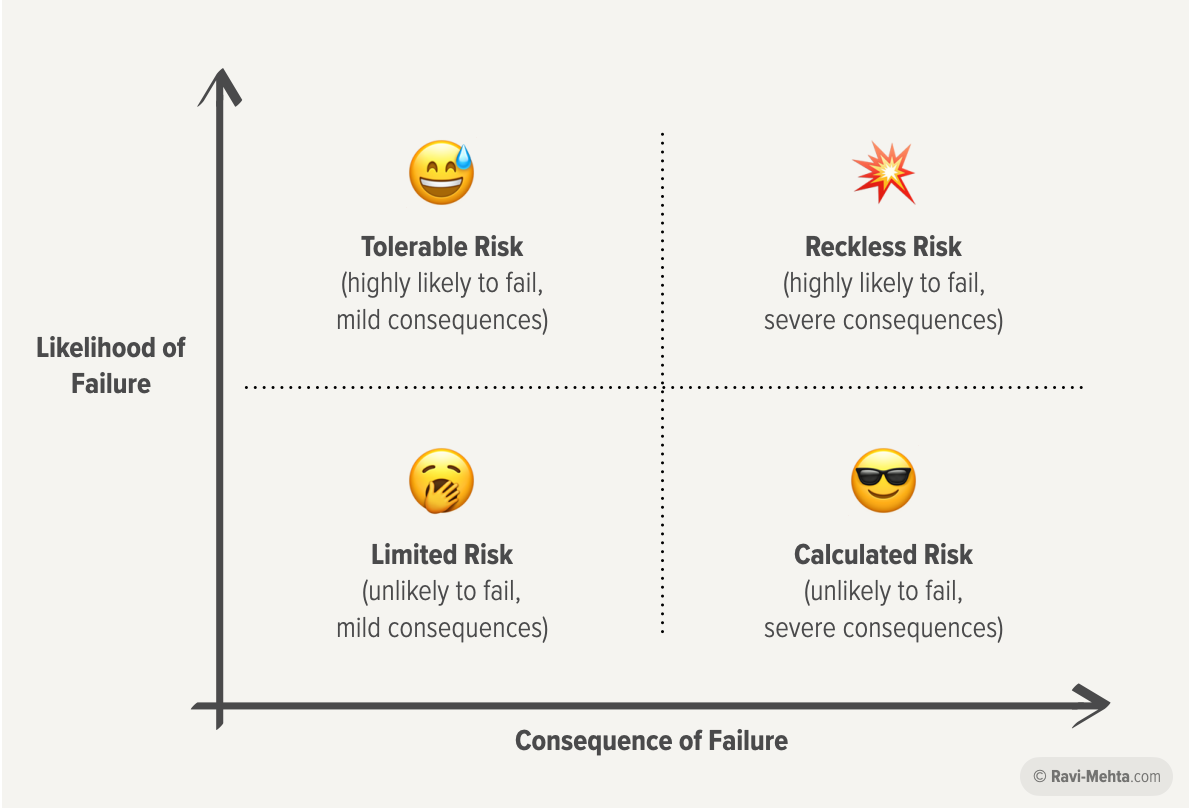

Let’s look at the first two factors together — because they have an important relationship. They are distinct concepts, but our lizard brain often conflates the two.

Consider car crashes versus shark attacks. Most people are more scared of shark attacks than car crashes — but the risk of driving to the beach is far greater than swimming in the ocean. There are around 70 shark attacks a year worldwide, and about 6 million car accidents per year in the US alone. Shark attacks are very unlikely, but the consequences of being attacked by a shark are always severe. Our fear center has a hard time separating the likelihood of risk from the consequence of risk, and so we need to focus on understanding the difference when we make decisions.

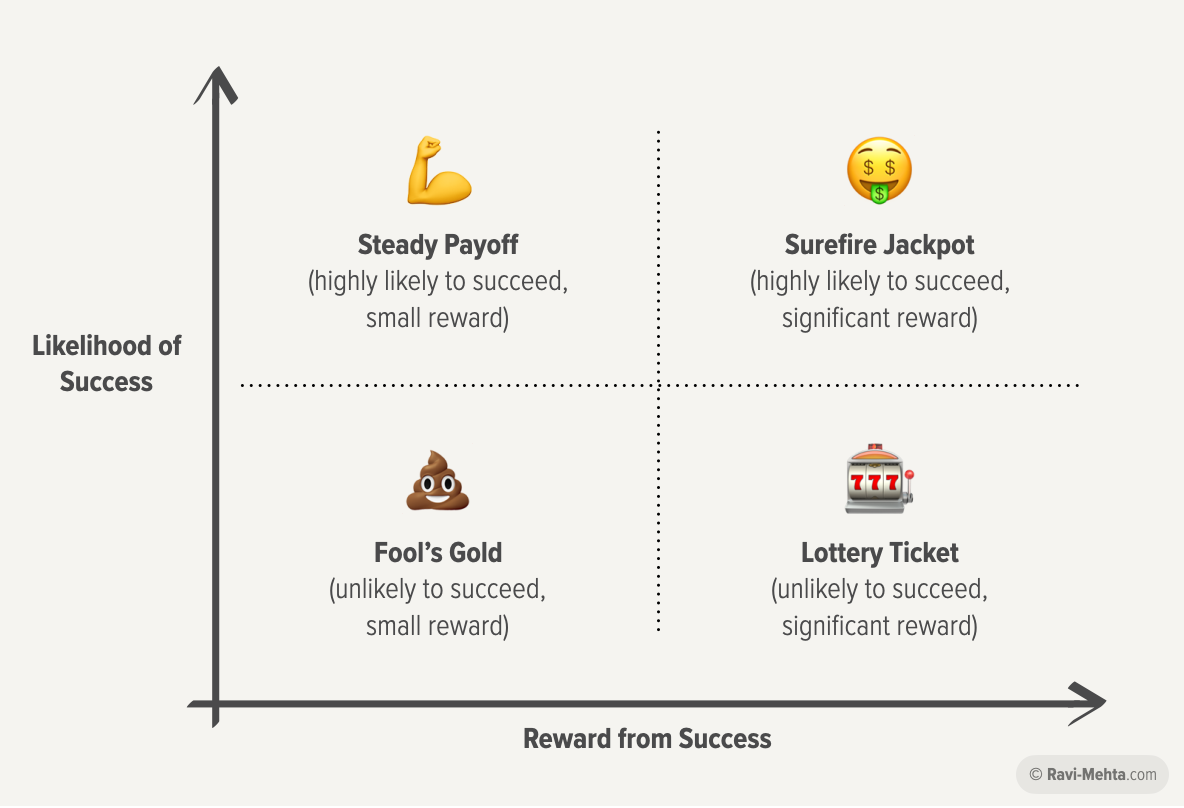

We can use a simple two-by-two matrix to plot the difference between the likelihood of an outcome vs. the consequence of an outcome. This is often used to assess risk (in other words, the failure case), but can be equally helpful in understanding rewards. Let’s look at how to use this tool to assess some common risks.

We’ll start with the riskiest quadrant — a decision with a high likelihood of failure and a high consequence of failure. These are reckless decisions. For example, a person climbing Mt. Everest without proper training would fall into this category – their lack of training leads to a high likelihood of failure and the consequence of failure is injury or death.

With proper training, a person can shift the risk profile. The consequence of failure is still high, but training can help a person lower the probability of failure. In this case, training helps a person move the decision from reckless to calculated.

There are decisions that have a high likelihood of failure, but a low consequence. A kid learning to ride a bike falls in this category. The risk is tolerable – they can always get up, dust themselves off and go back to it.

Lastly, we have safe decisions – decisions where the likelihood of failure and the consequence of failure are both low. These are the easiest decisions to make.

We can use this same approach to assess the success case by looking at the probability of success vs. the rewards from that success.

Remember, the success case and the failure case are not necessarily equal and opposite. A low probability of failure may not mean a high probability of success. A significant consequence of failure may not be counterbalanced by significant rewards. Not fair, but that’s life.

Good strategic thinking embraces that reality.

Latency

Once you’ve assessed probability and consequence, the next factor to consider is latency - How long will it take to recognize success or failure? Some decisions lead to an outcome immediately, and others take some time to play out.

People are really bad at dealing with latency between action and outcome. The classic example is trying to adjust the shower temperature if it's delayed – people get frustrated and overcompensate leading to a whipsaw between water that is way too hot and way too cold. In other cases, people underreact — not realizing that a decision is going off course before it’s too late.

We can greatly improve decision-making by identifying these latencies and putting in place systems to proactively monitor how a decision is progressing.

Again, we need to think about latency separately for the success case and the failure case. In some scenarios, success can play out very quickly (such a a successful product launch) but it may take time to recognize that a launch has failed. In other scenarios, such as the outcome from a surgery, the opposite is true — failure is immediately apparent but it can take months or years to evaluate success.

Cost

Another very important factor to consider is cost — How much will it cost to achieve success or failure? In particular, we want to minimize the cost to reach failure so that we can quickly and inexpensively learn what isn’t working. This is the first principle underlying the concept of the MVP or “minimum viable product”. A good MVP is the least costly way to prove out an idea – the least costly way to achieve success or recognize failure.

Reversibility

Jeff Bezos has described two different types of decisions: one-way doors and two-way doors. Some decisions can be reversed, and others cannot. We should make decisions differently depending on whether that decision is a two-way door or a one-way door.

Jeff goes on to say that most decisions are two-way doors. In these cases, we should have a bias towards action. We can make these types of decisions quickly without worrying about the downside — we can always redo the decision in the future.

But this is not always the case. There are some decisions that are one-way. We need care and conviction before making these types of decisions — because there is no going back.

Let’s look at an example. The decision on whether to launch a product at the end of the quarter is typically a two-way door decision. If we ship the right product and a lot of people use it and love it, that’s a success. But if we ship the wrong product and people are frustrated, that’s OK. We can iterate on it. So we can turn around and walk back through that same door.

On the other hand, the decision to do a Product Hunt launch for that product is a one-way door decision. If we launch and the product isn't ready, then we’ve used up our one shot. In this case, we need to carefully consider whether we are likely to be successful and only make the decision when we have high conviction.

Second-Order Effects

The last factor we need to consider is the second-order effects of our decision — We need to ask ourselves “What is now possible as a result of success or failure?”

People often only think about the immediate outcome of their decision. In chess, the #1 factor in a player’s ability to win is how many moves ahead they are able to think — in other words, their ability to understand second and third-order consequences. This is an important part of making strategic decisions. We need to think about the sequence of options, outcomes, and opportunities that come from an initial decision.

Two of the most important second-order consequences to consider are optionality and feedback loops.

Many decisions can increase or reduce optionality. We need to imagine a future world impacted by our decision. What options have opened up and what options have closed? For example, the decision to lower prices may open up the option to sell to a different customer profile, but may also take high-cost customer acquisition channels off the table.

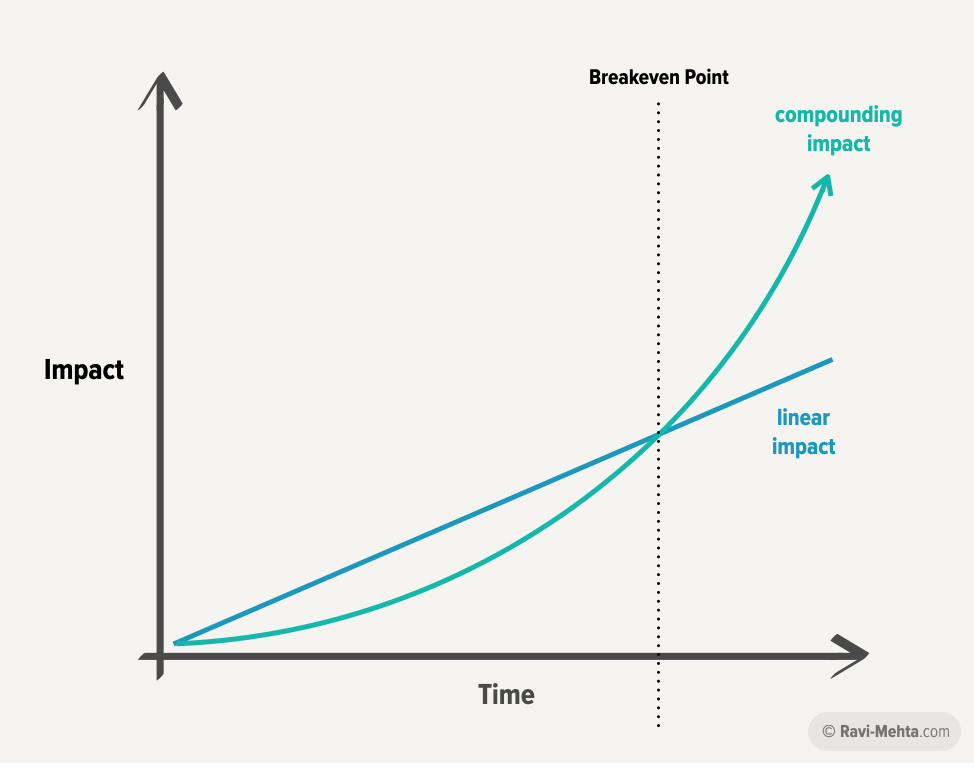

Feedback loops are another example of second-order effects. Some decisions have one-time results so it’s pretty easy to weigh the return on investment. Other decisions lead to outcomes that compound over time. People often underestimate the long-term return on decisions that create feedback loops. This is exacerbated by the fact that feedback loops often have some initial latency.

Decision analysis

Ok, enough theory! Let’s try putting this into practice with the decision you need to make. I’ll walk through how I used this approach to decide to start Outpace. As we go through the analysis, think about the decision you need to make and how you’d answer each of the questions we consider.

In 2020, I needed to decide what I wanted to do next in my career. I had left my role as Chief Product Officer at Tinder. The natural path was to look for another product executive role at a late stage private or public company. But, I was feeling the pull of entrepreneurship.

I used this decision-making framework to help me make a pretty tough decision: “Should I start a VC-backed company?”. I’d be walking away from prominent, high-paying opportunities for a risky bet. Intuition wasn’t going to cut it — I needed to be analytical to make the decision and proceed with conviction.

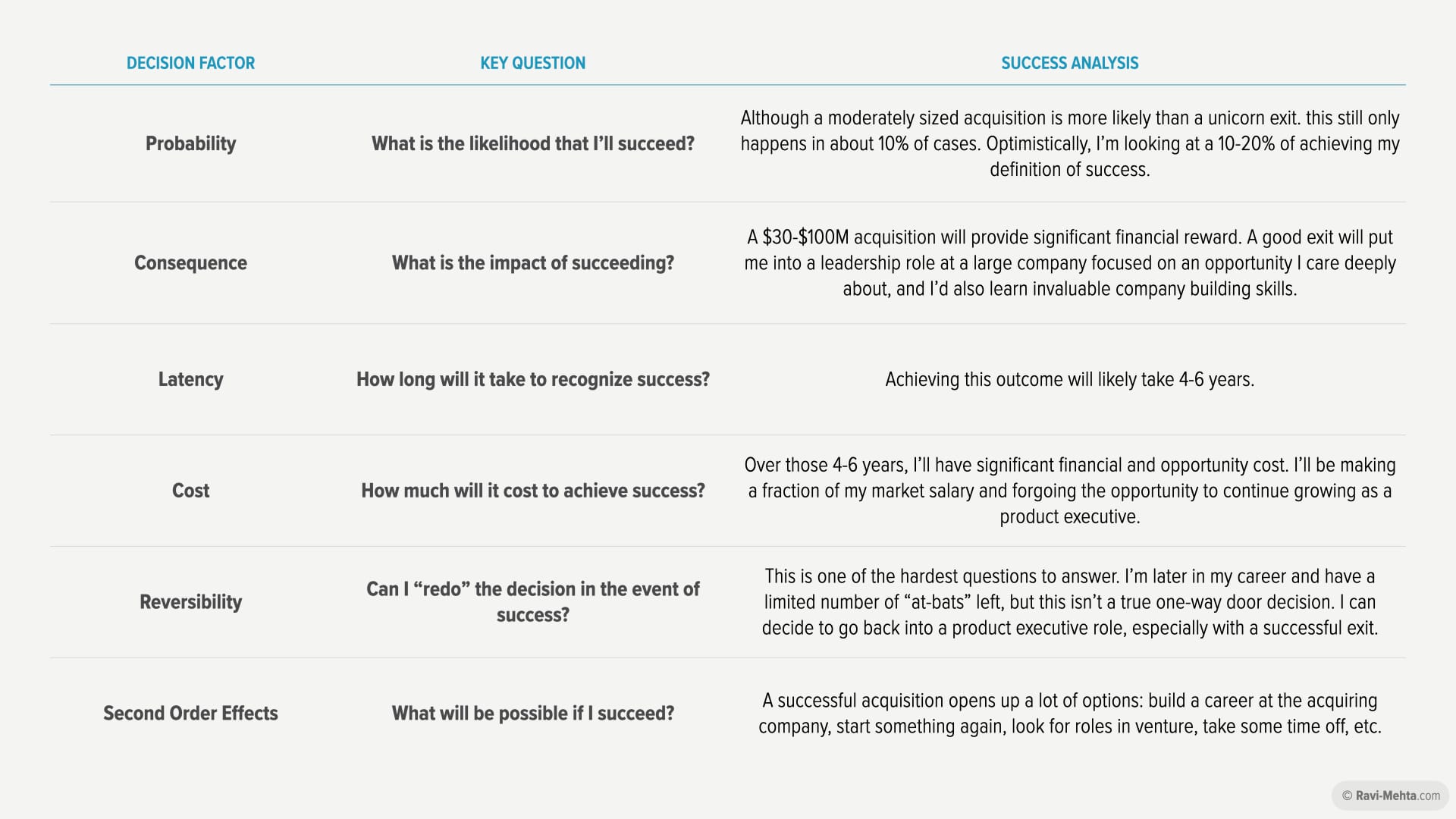

Analyzing success

We’ll start by considering the success side of our outcome tree. Why? I’ve found that people are pretty good at talking themselves out of any decision. Fear of failure is a powerful demotivator. Starting with the positive can help us visualize what we want to achieve and put our decision into a more balanced context.

In my case, I needed to start by defining what success looks like for starting a company. The goal of venture firms is to return their entire fund with a single investment. They need a couple of massive returns to pay for all the investments that go to zero. So, success often begins at the $1B valuation mark.

I believe entrepreneurs need to define their personal success differently. Venture firms have a portfolio of bets, so their risk/reward profile averages out. Successful VC firms return about 20-35% annually — much less than the multiples they need to underwrite for each startup they back.

Personally, I defined success as a $30M-$100M acquisition by a company I wanted to be a part of — a reasonable outcome even in the risky world of VC-backed startups. I was striving for much more, but that high case was outside the outcome tree I wanted to consider when making the decision.

Now that I had defined what success looks like, I considered each of the decision factors

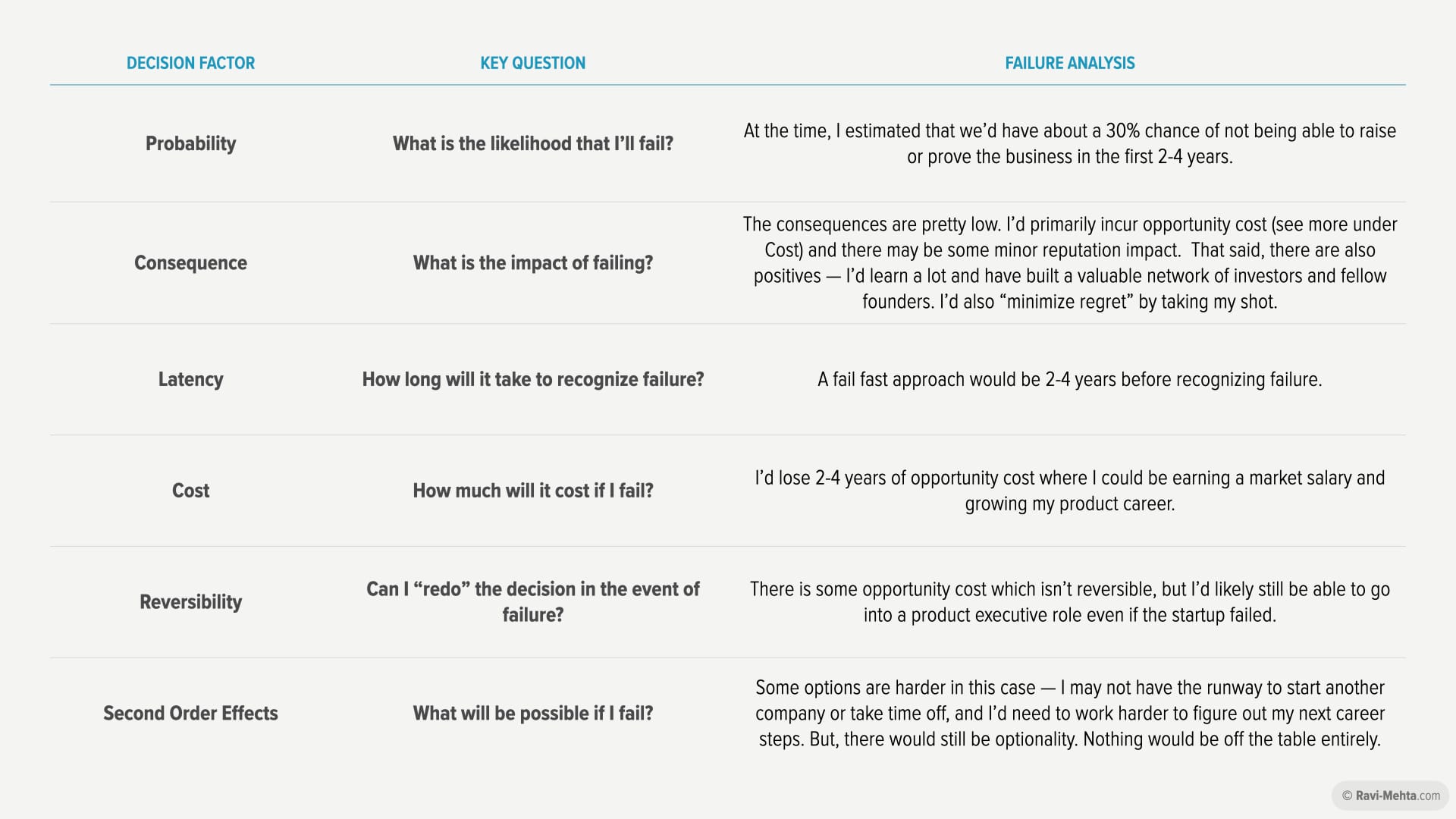

Analyzing failure

Surprise, surprise! Building a $100M company is a pretty nice outcome. Now let’s look at the same decision through the lens of failure. I know, thinking about failure can be uncomfortable. But, the work you do now will help you make the very best decision.

Remember, the answers to these questions about failure may be quite different than your answers about success. This insight into the different outcomes is often overlooked, but always critical.

As I thought about what failure would look like, I arrived at a critical insight. In the world of startups, it’s possible to fail fast or fail slow. I’ve seen entrepreneurs spend years chasing an opportunity, pushing against headwinds the entire way. There are some cases where this pays off. For example, Noom didn’t take off until about 10 years after the company was founded. But that’s the exception, and many founders I spoke with don’t regret failing — they just wish they would have failed faster.

So, I thought about what causes startups to fail: 1) failure to achieve product/market fit and 2) failure to find a scalable growth strategy. I estimated that it probably takes 12-18 months to make a conclusive call on product/market fit and at least another 12-18 to reliably scale growth. This meant failing fast likely requires 2-3 years.

And what would that look like? It would either be failing to raise a subsequent funding round or making a tough call internally if the business isn’t working. There is maybe a 30% chance of this happening — so 10% probability that we succeed with a substantive exit, 30% that we wind down the company in 2-4 years, and 60% of something outside of our success and failure cases (likely an acquisition outside the target valuation of $30-$100M). Remember, the success and failure cases don’t need to add up to 100% — and probably shouldn’t.

The final analysis

This decision analysis process was incredibly helpful, and made my decision to start Outpace much easier. The success case was very tempting — there is lots of upside to building a company in terms of learning, financial rewards, network building, and a raw feeling of accomplishment. I’d actually gain a lot of that in the failure case as well — the consequence of failure came down to the opportunity cost of forgoing a market salary and hitting the pause button on my product executive career.

The analysis helped me reach two critical insights. Firstly, it was important to fail fast to minimize the opportunity cost of this decision. I needed to be careful about getting into “startup limbo” where the opportunity costs are racking up and success is not getting more probable.

Secondly, I realized that starting a company was a two-way door decision. I could always go back to a product executive role. But, importantly, I realized that NOT starting a company was a one-way door decision. I was never going to have a better opportunity to take the leap than that moment in 2021. I knew I’d regret not taking that opportunity.

How did it all work out?

As I write this, we’ve made the difficult decision to wind Outpace down after running out of runway. We have tried to raise our seed round during a historically difficult time for VC fundraising and, to make matters worse, economic uncertainty is weighing heavily on certain sectors including professional development. There are things we could have done differently to put us in a better fundraising position and give us more runway, but — as the saying goes — hindsight is 20/20 and that’s a topic for another post.

Not only did this framework help me get the conviction I needed to take the risk to start Outpace, it also gave me the perspective I needed to be at peace with the outcome.

Strategic thinking begins with first principles, not an MBA

We made it through a whole post about strategic thinking without mentioning competitive advantage, economies of scale, market power, network effects, game theory, or the myriad other concepts packed into stacks of strategy books.

These concepts are powerful shorthands to quickly describe and understand complex situations. But, they can all be refined down the first principles we just reviewed. Competitive advantage helps us understand the probability and consequence of success. Economies of scale is a way of thinking about latency and cost. Networks effects and game theory are tools for understanding second-order effects.

Strategic thinking becomes much less overwhelming when we break it down into a series of fundamental questions, and apply those questions to a specific decision. It’s not the domain of a rare few or something that requires years of study. The next time you’re faced with a strategic question, rev up your Decision Making Time Machine™️ and let me know how it goes.