This is a pivotal time for executives and entrepreneurs. As we start to relax social distancing, each and every company will face a reckoning — quickly, we'll be able to separate the resilient from the walking dead.

“Antifragile” is the buzzword of our day. But, what does it mean to be antifragile? What makes a company antifragile?

Certainly, some companies have benefited from this moment. Zoom is the first to come to mind. But was Zoom merely fortunate, or are they antifragile?

Video conferencing is a crowded and commoditized space. Yet, it is Zoom that seized the moment by scaling from 10M to 200M daily users in a few weeks. Why has Zoom benefited disproportionality relative to Google, Facebook, and other companies that should have done better?

Trader Joe's is another example. The enigmatic grocer has refused to add online delivery and pickup in the face of coronavirus. Despite bucking the coronavirus playbook, they've come out ahead with increased profits — some of which they are passing on to workers.

Meanwhile, Uber and Lyft have failed to adapt. Together, they own the most sophisticated transportation and logistics capability that has ever existed — one perfectly designed to meet the rapid, point-to-point delivery needed to support a population forced to stay in place.

Why has the coronavirus pandemic made some companies stronger and blown others to bits?

Nassim Nicholas Taleb is a polymath -- the Internet age's equivalent of a renaissance man. He is a physician, an author, a mathematician, a scholar, and a wealthy hedge fund manager. Nassim was born into a well-known family in Lebanon during a period of peace and prosperity. But that did not last. In the mid-1960's, the country's financial system began to collapse, and the country eventually descended into civil war.

At a young age, Nassim learned that worlds collapse. He's made a fortune betting on the inevitability of the impossible -- beginning with Black Monday, the 1987 stock market crash.

He has shared his contrarian views on uncertainty and risk in a series of five books. His 2012 book, "Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder", introduces the concept:

"Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better."

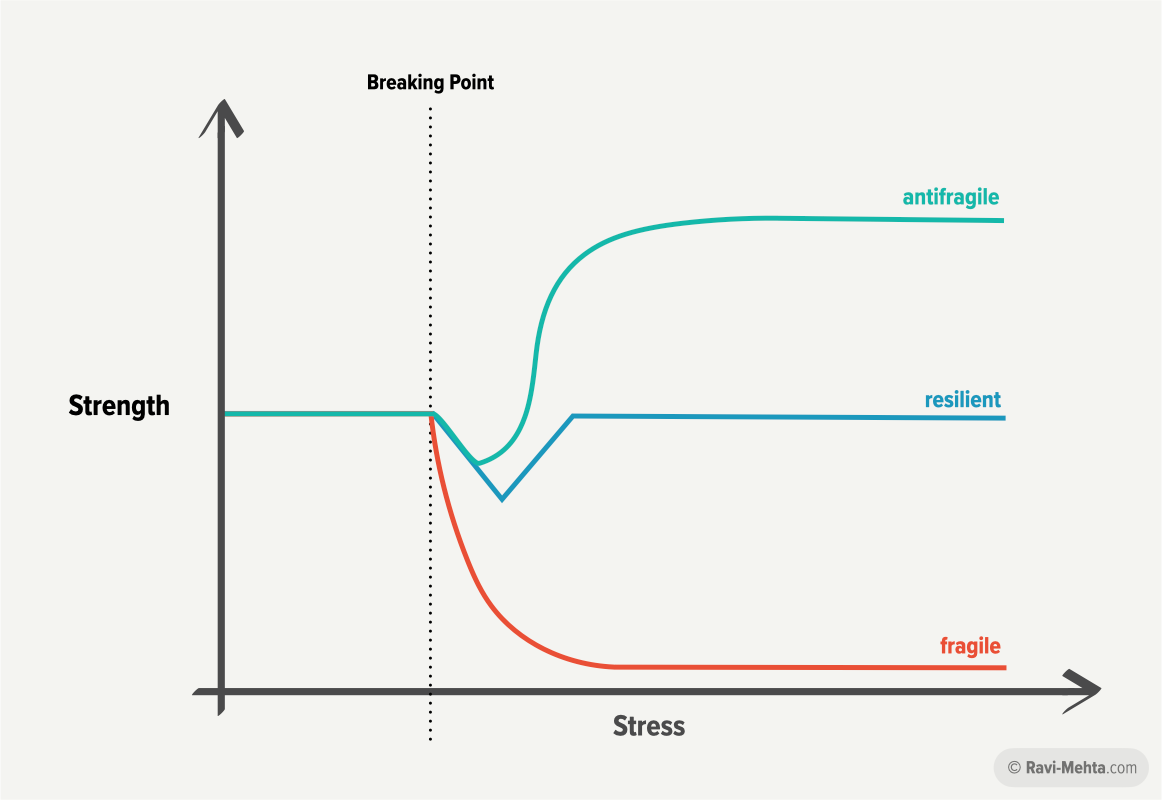

Nassim distinguishes three concepts: fragility, resilience, and antifragility. Each defines a different way in which a system reacts to stress.

Let’s imagine a system made of glass that receives stress from a hammer. If you lightly tap the glass with the hammer, nothing will happen. The glass remains equivalently strong. As you increase the stress, the glass remains strong until it reaches a breaking point. At that point, the glass shatters, and its strength goes to zero.

Fragile companies are like glass. Under the right amount of the right kind of stress, they break. We saw this with the banks in 2008. Today we see this same fragility in the airlines, many of which will go bankrupt in the next couple months.

Resilient companies are like rubber. They deform when subjected to stress, but bounce back once the stress is removed. Zillow is an example of a resilient company. They weathered the 2008 financial crisis and built a system that can withstand downturns in real estate — a system that includes $2.5B stashed under their mattress.

Antifragile companies are like muscle. Bodybuilders know that muscle tears under the right kind of stress, but it builds back up — stronger than before. Amazon is an antifragile company. Yes, Amazon has benefited from increased demand, but that radically increased demand could have easily broken a fragile company. Instead, Amazon has leveraged its diversified business portfolio and rapid adaptability to seize the moment and emerge stronger.

People react to stress in very different ways. Some people amplify stress, making themselves fragile under the wrong circumstances. Others have trained themselves to turn stress into a catalyst for growth.

Similarly, companies react to stress in very different ways. Companies — knowingly or unknowingly — design themselves to be fragile or antifragile.

Antifragile companies share three design patterns:

- They build diversified, synergistic businesses.

- They prioritize capacity over efficiency.

- They leverage human adaptability.

Antifragile companies build diversified, synergistic businesses.

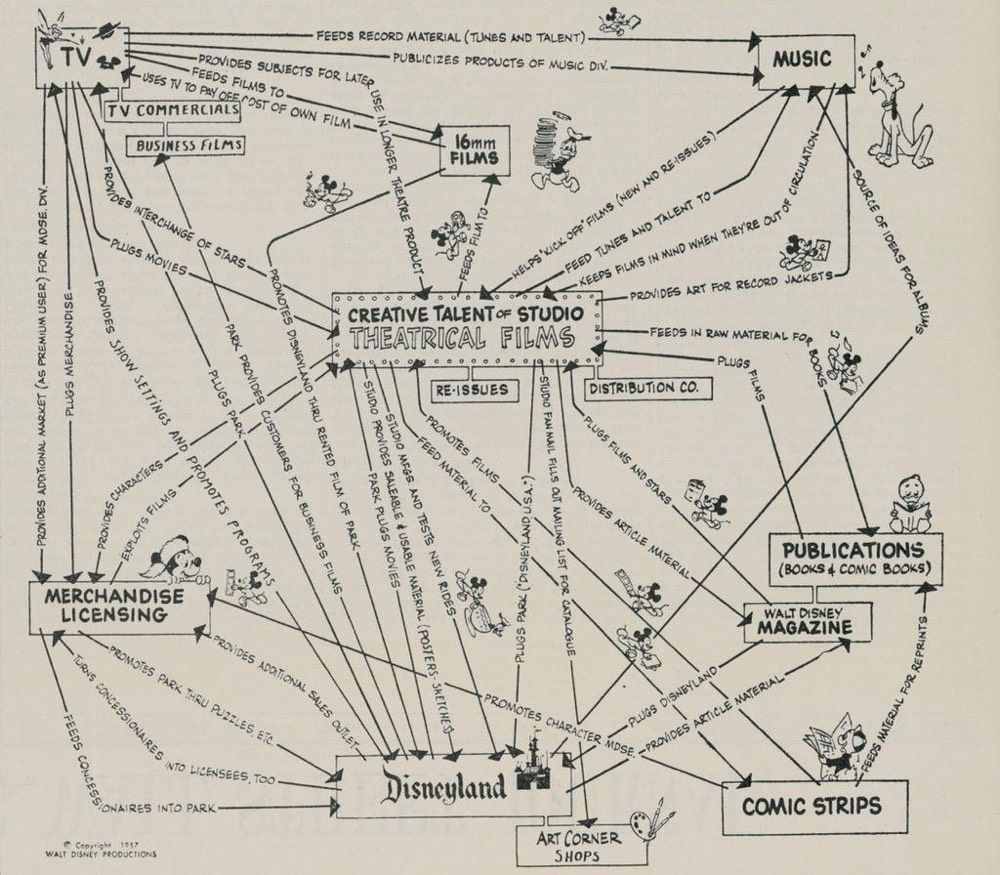

In 1957, Disney founder Walt Disney mapped out the strategy for his company. Disney’s “Synergy Map” was prescient. It defined the playbook the company has used for over 60 years. In that time, Disney has grown over 500 times more valuable. Meanwhile, many of the top companies in 1960 have collapsed.

The “Synergy Map” is a model of antifragility. Many companies seek to diversify, but few companies diversify as intentionally as Disney. Disney has capitalized on its strength in creating entertainment franchises and reinforced that strength by extending those franchises into mutually reinforcing businesses.

The pandemic has been devastating to Disney’s travel and theme park businesses, but its growing streaming business is a counter-balance. Similarly, Amazon’s increasingly large physical retail business is vulnerable to the pandemic, but counter-balanced and reinforced by its e-commerce strength.

Even limited diversification can help. Today, Uber is benefiting from it’s investment in Uber Eats, a smart, synergistic diversification of its transportation capability. On the other hand, Lyft is suffering from the fragility of being a mono-product business. Their stock has declined 27% since mid-February, significantly more than Uber’s 17% drop over the same period.

James Clear, author of the bestseller Atomic Habits, published this recently:

The paradox of risk:

(1) Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. If you lose the basket, you lose it all.

(2) Don’t put your eggs in too many baskets. The more baskets you manage, the less energy you can put into each one. It’s risky to do things halfway.

Diversified, but focused.

It’s sage advice. But let’s go a step further. What happens when the egg you put in one basket makes all the eggs in all the baskets more valuable?

That’s not just a recipe for resilience; its a recipe for antifragility.

Antifragile companies prioritize capacity over efficiency.

Chamath Palihapitiya, CEO of Social Capital, made $1.7B last year. He knows a thing or two about investing.

In a recent Q&A with Anthony Pompliano, Chamath discusses how the US has become dependent on China for simple, necessary goods like the PPE required to protect US healthcare workers during the pandemic: “In our hellbent desire for efficiency, we’ve empowered certain countries and economies to have incredible leverage over us… We have to pivot to a much more resilient model.”

Chamath goes on to explain that the more resilient model means “repatriating the supply chain back to the United States” — a move that will increase costs and increase prices, but at the benefit of higher employment and a more resilient domestic economy.

Many companies have made the same tradeoff as the US government. In a ruthless quest for efficiency, they’ve increased their “value” in the eyes of Wall Street, but made themselves more fragile in a world defined by Black Swan events.

Consider the extreme example of Groupon. Since 2011, they have sold both local experiences and physical goods. Despite being relatively early to the e-commerce game, they have struggled in recent years.

On Groupon’s February 19th earnings call, Rich Williams (former CEO of Groupon) said of the Goods business : “It has effectively become a distraction in which we can no longer compete and that we cannot afford, as it has taken roughly 40% of our impressions to deliver roughly 20% of our gross profit.”

So, on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic, the company decided to shutter its physical goods business and focus solely on local experiences. In the face of the greatest disruption to local business in history, they chose to focus on the efficiency of a meaningless ratio (gross profit per impression) rather than the growth opportunity latent in nearly half their traffic.

They chose fragility in pursuit of efficiency.

Less than two months after that February earnings call, Groupon announced plans to layoff 2,800 employees (40% of its staff). Today, they have walked back from total closure of their Goods business. However, it may be too little too late. They’ve largely missed the opportunity to provide delivery, pickup, and gift card products. Sometimes choosing efficiency is the least efficient choice of all.

Contrast that with Zoom. The company successfully scaled from 10M daily users to over 200M daily users in a few weeks. How were they able to meet crushing demand for a service that is technically taxing even in the best of times?

“Zoom traditionally keeps about 50 percent more capacity on its network than its maximum actual usage, he said, and the team has been busy in recent weeks maintaining that cushion.”, said Alex Guerrero, senior manager of SaaS operations at Zoom, in a recent interview with DataCenter Knowledge.

In computer science, redundancy is the key factor in resilience. Software designers know they face an inescapable choice between resiliency and efficiency.

The same is true in business, but executives are not as forthright about that choice. To make matters worse, Wall Street tends to reward efficiency more than resilience. After all, efficiency shows up in financial statements, but resilience does not.

As a result, most of the US economy has chosen to operate at the edge of efficiency. It’s a choice that has eviscerated our domestic manufacturing capacity in search of lower prices and higher profits. Today, the US can no longer manufacture at scale even simple things like the masks, gowns, and gloves needed to keep our healthcare workers safe.

Yet, parts of the US economy are antifragile. Companies like Amazon don’t run at their efficient frontier. Jeff Bezos has set the expectation with Wall Street that the capacity to experiment is more important than the efficient production of profit, “Failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment.”

Antifragile companies leverage human adaptability.

Humans are by far the most adaptable entities on the planet — more so than any algorithm. But, advances in technology and the ruthless quest for efficiency are giving rise to a new trend of treating humans like cogs in a machine.

Uber treats its drivers in this way. Each human is a commoditized, interchangeable part within Uber’s machine. Those humans are even subject to planned obsolescence — Uber has invested billions of dollars to develop self-driving cars.

Uber built intelligence into its algorithms instead of taking advantage of the collective intelligence of its human drivers. They designed a system that is, by far, the most efficient way to manage the ebbs and flows of passenger markets. The intelligence of their algorithms far surpasses the intelligence of their people, but only within the confines of the world they planned for.

When their world changed, Uber’s machine broke. If you treat humans like cogs in a machine, then that machine breaks under stress - as any machine would.

Uber has missed the opportunity to tap into the adaptability and entrepreneurial spirit of their vast driver network.

In contrast, Airbnb — another “sharing economy” company — treats their hosts like people. Within weeks, they were able to work with their hosts to deliver Online Experiences, live video experiences like “Dance Like a K-Pop Star” and “Cooking with a Moroccan Family”.

Interestingly, the idea for Online Experiences came from hosts, not Airbnb. As David Pogue explains in a recent New York Times article, “When the company suspended those risky in-person interactions in March, the guides, suddenly unemployed, proposed adapting their classes to video.” After a weekend of binging these experiences, David raves, “This new format is an ingenious, inexpensive way to carry you and your family away during lockdown, and even — why not? — long after the present plague passes.”

Trader Joe’s is an other company that taps into the ingenuity of its people. The company has been careful to adapt to the global pandemic in a way aligned with its employee-centric ethos. They avoided adding delivery and curbside pickup. Tara Miller, Trader Joe’s Marketing Director, explains in a recent interview with Reader’s Digest:

“The bottom line here is that our people remain our most valued resource. While other retailers were cutting staff and adding technologies like self-checkout, curbside pickup, and outsourcing delivery options, we were hiring more crew, and we continue to do that. We know that this period of distancing will end and when it does, our crew will be in our stores to help you find your next favorite product, just as they’ve always been.”

Anecdotally, Trader Joe’s has been the best experience I’ve had shopping during the lockdown. Their stores are fully staffed and better stocked than most other grocery stores. At our local store, one employee greets you and hands out sanitizer, while another wipes down your cart. The employees have created one-way lanes, similar to Ikea, that walk you through the store — giving each guest an opportunity to browse the entire store while eliminating the crowds and chaos common to other stores.

The staff are friendly and helpful. On my most recent visit, an employee escorted a young man throughout the store helping him grocery shop for what seemed like the first time.

Their focus on people is working. Trader Joe’s has announced that they are setting up a special bonus pool due to an unprecedented increase in sales.

Antifragile companies not only tap into the ingenuity of their workforce, they tap into the ingenuity of their customers. Online dating apps were built to help people meet in real life, but have seen increased usage as users flock to the apps to find social connection in a time of social distancing. Companies have quickly added features, such as Bumble’s Virtual Dating badge, to support new customer behaviors.

Roblox is perhaps the best example of customer-driven adaptability. The tween-focused online gaming platform is like games such as Minecraft, but with an important twist.

Roblox features a developer platform that caters to everyone from kids who want to build their own worlds to professional developers making serious money. In 2019, Roblox paid out over $110 million to its developers. Alex Balfanz, the 20-year-old creator of Jailbreak (a game played over 3 billion times), has reportedly made over a million dollars from his creation.

Roblox saw usage surge 40% in March as tweens turned to the game to replace playground time and playdates. But Roblox is more than resilient — it’s antifragile. The surge in usage has energized a rich ecosystem of creators who are making Roblox better everyday.

Stress transformed into strength.