On June 24th, I participated in the #FirstPrinciples speaker series organized by Gojek. Below are my slides and notes from the talk.

I discussed what I’ve learned about making great products.

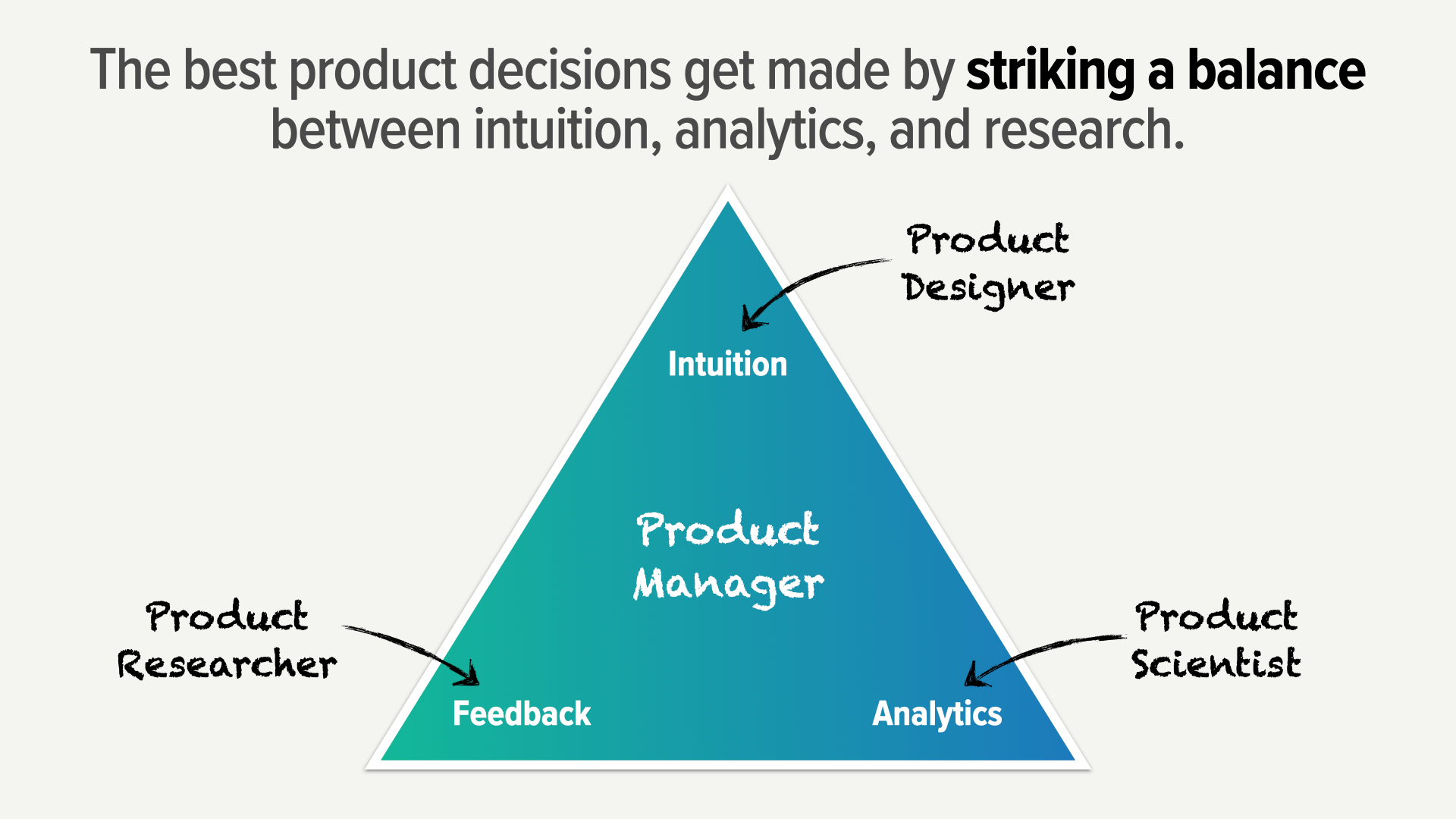

Making great products is the outcome of making great decisions. As product builders, we base decisions on three pillars: intuition, analytics, and customer feedback.

Making great products is the outcome of making great decisions.

The best decisions are made when they draw from all three pillars, but striking a consistent balance is difficult. People, teams, and companies tend to bias towards one type of decision making.

I’ve pulled together examples from across the industry to illustrate the three pillars of product decision making and why it’s so hard to get it right all the time.

Illustrations by Katerina Limpitsouni on unDraw

I’ve spent my career building consumer tech products that impact millions of users.

Along the way, the thing I’ve loved most is building teams and coaching PMs. Many of the folks I hired directly out of school are in Director and VP level roles today, and that outcome is better than any product feature I’ve shipped.

Over the last several months, I’ve been writing about and presenting what I’ve learned to help PMs and product leaders accomplish their goals.

Great products are the result of great decisions — decisions that deliver value for customers and the business.

I believe strongly that the best product builders don’t just ship features, they deliver business impact.

Product managers make decisions using some combination of three inputs: 1) intuition, 2) analytics, and 3) feedback.

The best products get made when decisions are informed by those three inputs in a balanced way.

However, striking this balance is extremely difficult. Individuals, teams, and companies often bias towards a particular mode of decision-making. This bias blinds companies to the true nature of the market and opens them up to disruption.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these modes of decision making.

Decisions made using intuition are based on a sensibility about what a great product looks like for the customer. This sensibility can be based on the tastes of an individual or institutionalized into company culture.

Often, these intuitive decisions are made despite limited data or contrary to popular beliefs. Good intuitive decision making can result in break-through products that have a disruptive impact on their market.

Most successful products start with an intuitive insight. Google began with the insight that the quantity of information on the Internet was exploding and there needed to be a better way to search that information.

What are some other examples?

Apple is one of the best examples of intuition-driven decision making.

Throughout its history, Apple has made successful products based on an intuitive sense of what the market wants.

People often forget that Steve Jobs was fired from Apple.

Shortly after returning to Apple, Steve Jobs began dreaming big—thinking about where the next great Apple product would come from.

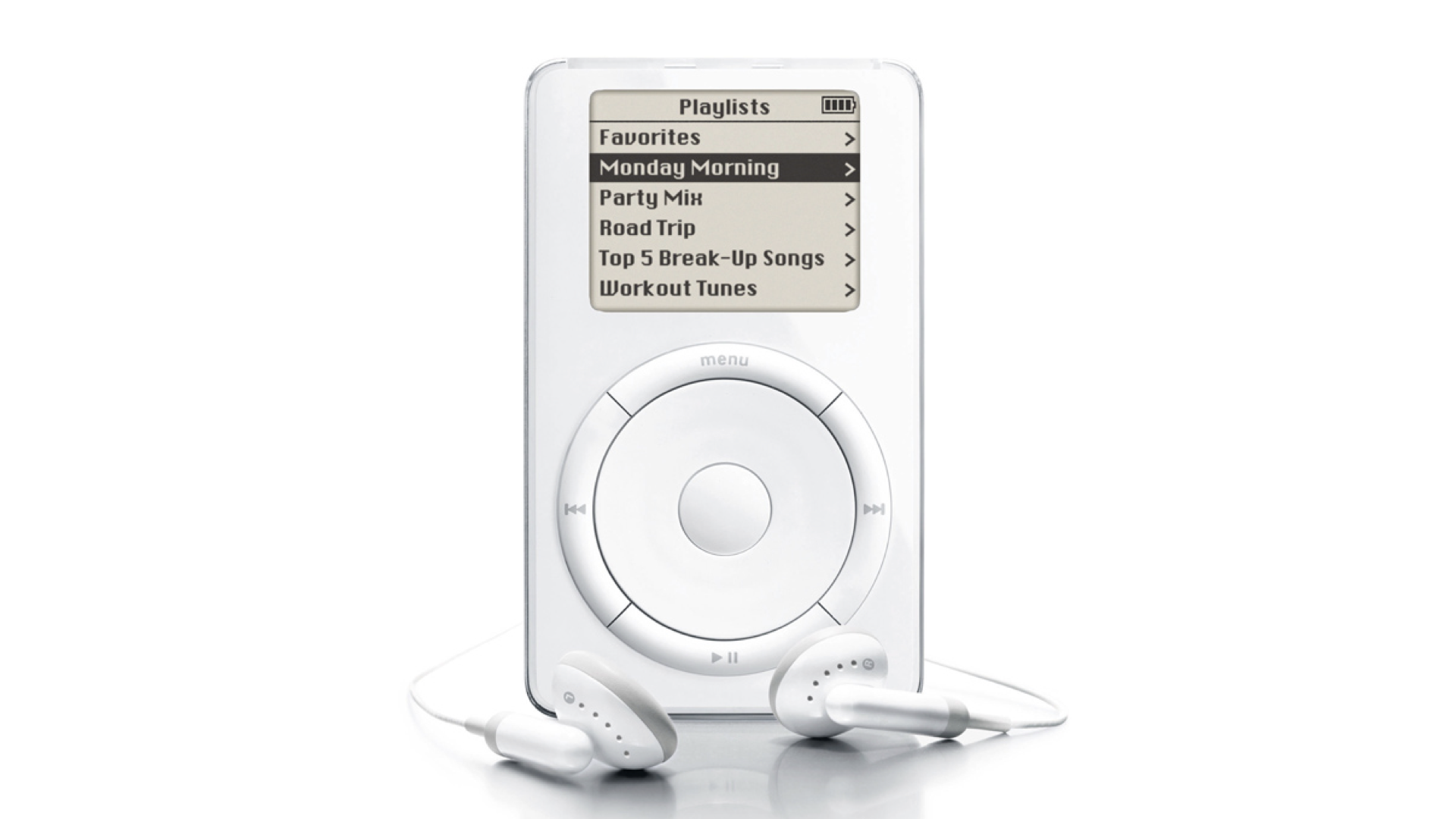

Steve had always loved music and was disturbed by the awkward state of the market. It was littered with ugly, ill-conceived devices that couldn’t deliver on the promise of digital music.

Intuitively, Steve felt Apple could do better.

With the iPod, Apple introduced a radically simpler MP3 player.

While the iPod was simpler, it was not simple.

Apple used its hardware savvy to solve important customer problems—the iPod was smaller, had more capacity, had a longer battery life, and was faster to load with music than other devices.

The iPod changed the face of digital music and turned Apple into a rocket ship.

In 2002, Apple was valued at $10B. Today, it has grown nearly 100 times. With a market cap of more than $1.5T, Apple is firmly planted as one of the most valuable companies in the world.

But intuition often flies in the face of prevailing wisdom.

A commentator remarked of the iPod, “All that hype for an MP3 player? Break-thru digital device? The Reality Distortion Field™ is starting to warp Steve’s mind if he thinks for one second that this thing is gonna take off.”

Intuitive insights are most valuable when the rest of the world is in the dark.

Peter Thiel refers to this as “knowing a secret”. He believes ground-breaking companies are formed when the founder knows a secret the rest of the world hasn’t yet discovered.

Apple’s intuition was a leap, but it was grounded in good strategy and smart analysis of a large market.

Apple correctly intuited that “1000 songs in your pocket” would change how people consume music—turning the MP3 player into a constant companion.

This intuition informed crucial beliefs that have underpinned Apple’s strategy to this day:

- Apple believed people would pay a premium for devices that play such an important part in their lives—a good match with their premium brand positioning. The high margin would give them cash to re-invest in R&D—strengthening their lead in consumer hardware.

- Apple believed the iPod would be a beachhead into a much larger market of companion devices and services.

- Apple believed this was an opportunity to move the company from a computer brand to a lifestyle brand.

Good intuition builds great companies, but bad intuition can be destructive.

Let’s look at a recent example.

Evan Spiegel’s great strength is his intuition about what young users need from social media.

Evan’s intuition about ephemerality, messaging, and visual communication have led to Snapchat becoming one of the largest social platforms ever created and have changed the fabric of social media.

Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp rushed to follow suit. They added Snapchat-inspired Stories—leading some insiders to quip, “Evan is Facebook’s best product manager.”

In 2017, Evan and Snapchat went confidently into their next intuitive insight—“separating social from media” would streamline Snapchat to better serve two important, but distinct use cases.

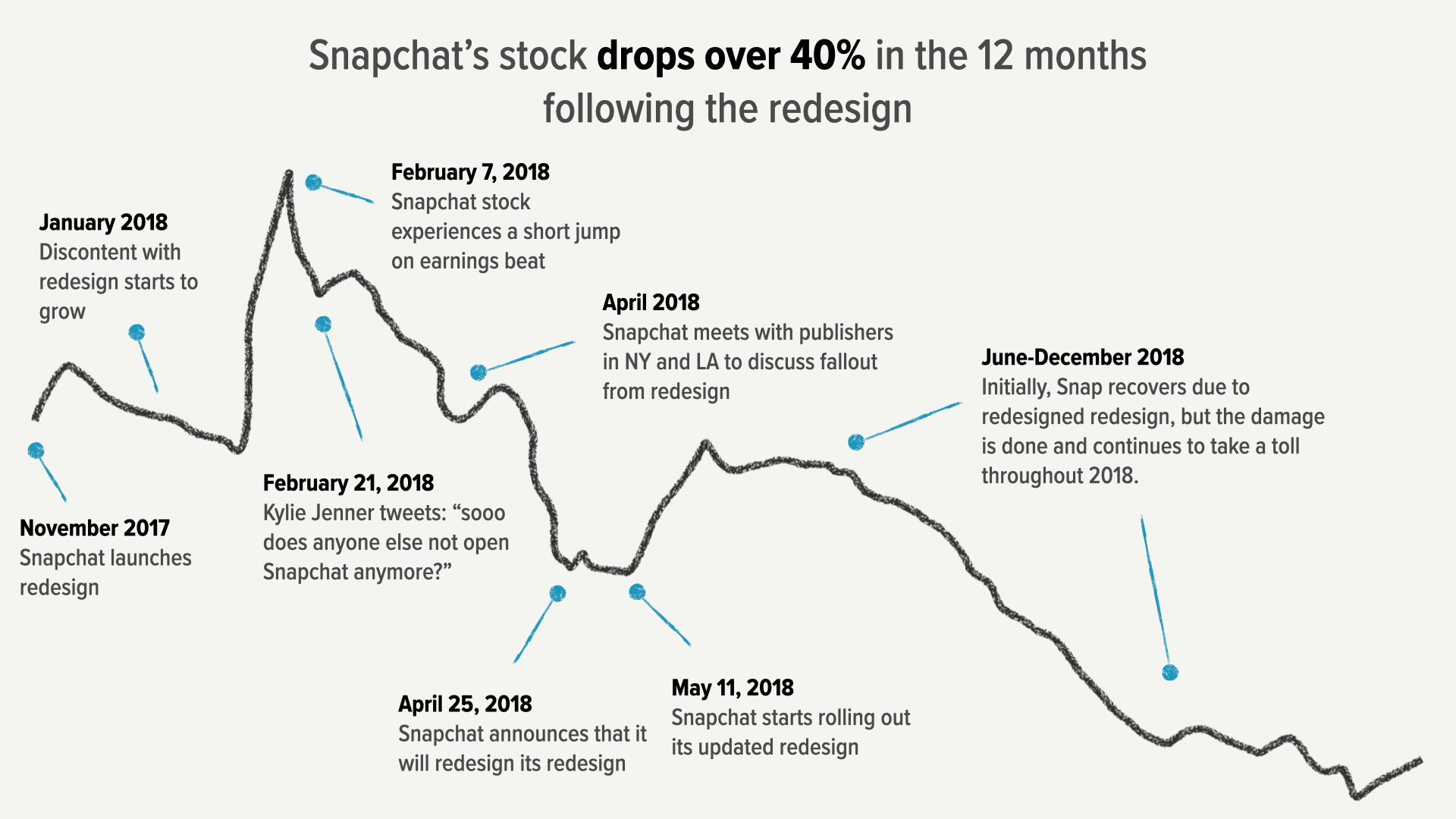

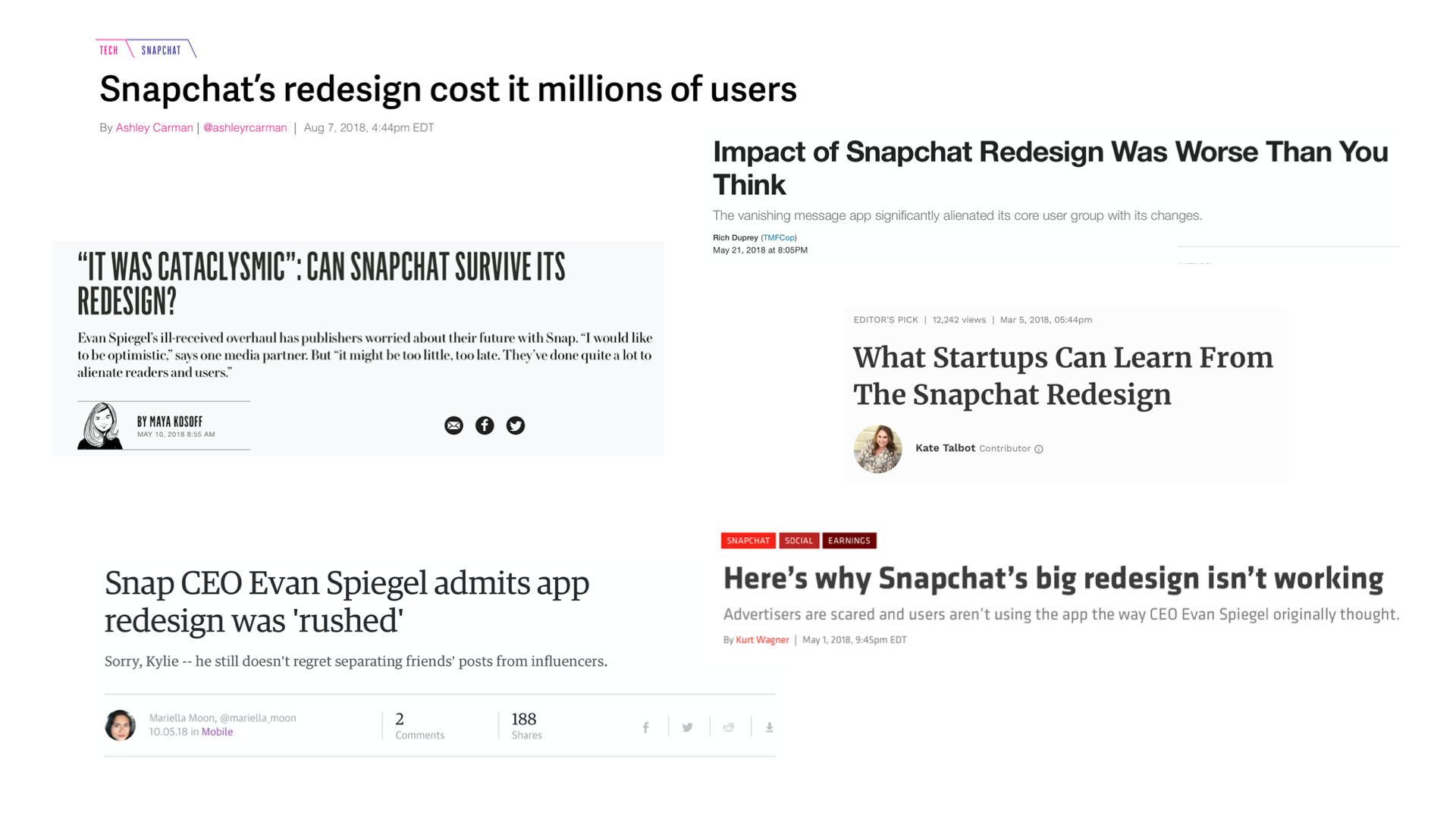

The Snapchat redesign did not go as planned. Snapchat over-relied on intuition and disregarded the negative signals from analytics and customer feedback.

Over the course of 2018, Snap was slow to react to a torrent of feedback from users, influencers, and publishers.

Customer feedback about the redesign was immediate and vocal. Customers voted with their feet. Snap’s engagement decreased across several key metrics.

Despite the clear signals, Snap took 5 months to announce changes. By that time, the damage was done and, for many people, Instagram had supplanted the role that Snapchat once held.

Snapchat’s decision to stick with the redesign despite controversy was reminiscent of Facebook’s decision to stick with the News Feed when it launched to controversy in 2006.

We’ll see in a few moments why Facebook’s redesign had a very different outcome than Snapchat’s.

Great companies are often built on massively-impactful, intuitive insights.

But the quality of intuitive decision making can be hard to evaluate, and teams who over-rely on intuitive decisions risk swinging and missing a lot.

As a result, the tech industry has put emphasis on analytics-driven decision making.

Snap learned the importance of analytical decision making in the aftermath of the 2017 redesign. They built a data-centric growth team that complements the company’s strong product intuition. The result has been a return to growth. Snapchat’s stock has increased over 4x in the time since it rectified elements of the redesign.

Let’s look at why analytics are so important.

Analytical decisions are based on the insights generated as customers use the product. Analytics is about more than reporting—knowing SQL is not enough.

Good analytics is grounded in actionable conclusions—in a causal understanding of why users behave the way that they do.

This mode of decision making is in fashion right now—both because the results of analytics-driven decision making are easy to quantify and because there is now more data than ever with which to make decisions.

Good analytics-driven decision making can provide the fuel that turns a spark into an inferno—that enables products to reach their full potential.

Facebook, particularly Facebook’s growth team, is an excellent example of analytics-driven decision making. Facebook has extended its initial product-market fit with college students to 2 billion people by rigorously applying testing and analytics to drive increases in reach, engagement, and monetization.

Let’s look at an example of this.

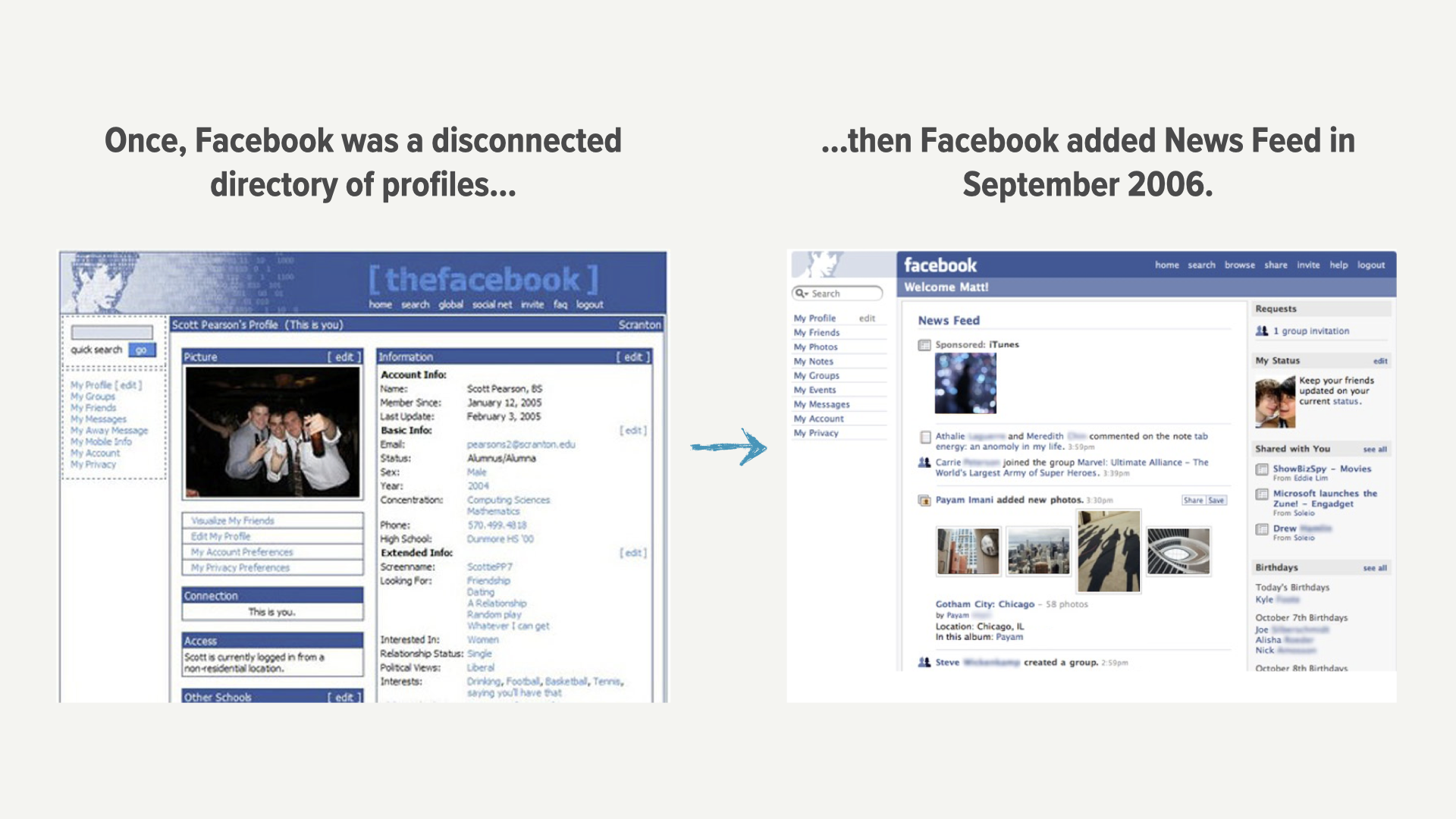

Once upon a time, Facebook was a disconnected directory of profiles.

Through its analytics, Facebook saw that users logged in and went through a repetitive and tedious process of checking all of their friends profiles to mine for updates.

Facebook felt they could productize this use case by building a new home page experience that aggregated updates all in one place: the News Feed.

Intuitively and analytically, Facebook was confident they had a big win on their hands.

What came next was a surprise.

The morning after launch, the News Feed team woke up to hundreds of thousands of outraged people.

Throughout the night, angry users had organized groups to petition Facebook to remove News Feed. The largest group grew to 284,000 members in under 24 hours. In one form or another, 10% of Facebook’s 8 million student users threatened to boycott the company.

It was one of the fastest and most viral backlashes to a product in history.... thanks to News Feed.

In a post, Ruchi Sanghvi, the Product Manager for News Feed, wrote:

We woke up to hundreds of thousands of outraged people. Facebook groups like “I hate newsfeed”, “Ruchi is the devil” had formed in the middle of the night. News reports and students were camped out in front of our offices. We had to sneak out of the back door to leave the office.

In this same post, Ruchi talked about poring over the Facebook logs to understand how the feature was going. She discovered:

Amidst all the chaos, all the outrage, we noticed something unusual. Even though everyone claimed they hated it, engagement had doubled.

While a vocal minority complained, the analytics told a different story. Other companies might have seen a disaster or succumbed to the PR onslaught. Facebook saw a win—thanks to analytical discipline.

Facebook’s analytics mindset starts in the earliest phases. Many of Facebook’s top features, News Feed included, come from observing existing behaviors and creating functionality to support those behaviors.

Facebook’s true north is analytics—they judged the success of News Feed by the engagement impact, not the PR response.

Facebook watches data in real-time and moves quickly on it. While Snap waited months to respond to the backlash, Mark posted the same day to quell user concerns.

Many analytical companies become too incremental because of their reliance on data. Facebook tries to strike a balance. They’ve used data to inform the company’s big bets like the shift to mobile, the Instagram acquisition, separating Messenger from Facebook, and integrating Stories as a primary social format.

But, data alone would not have led Facebook to these conclusions. Intuition and customer feedback play a crucial role in Facebook’s product decision making process.

Analytics blazes the path to maximum potential, but over-reliance on data leads to incrementality.

Let’s take a look at an example of how companies that over-rely on analytics-driven decision making can become too incremental and miss out on the innovations that disrupt their market.

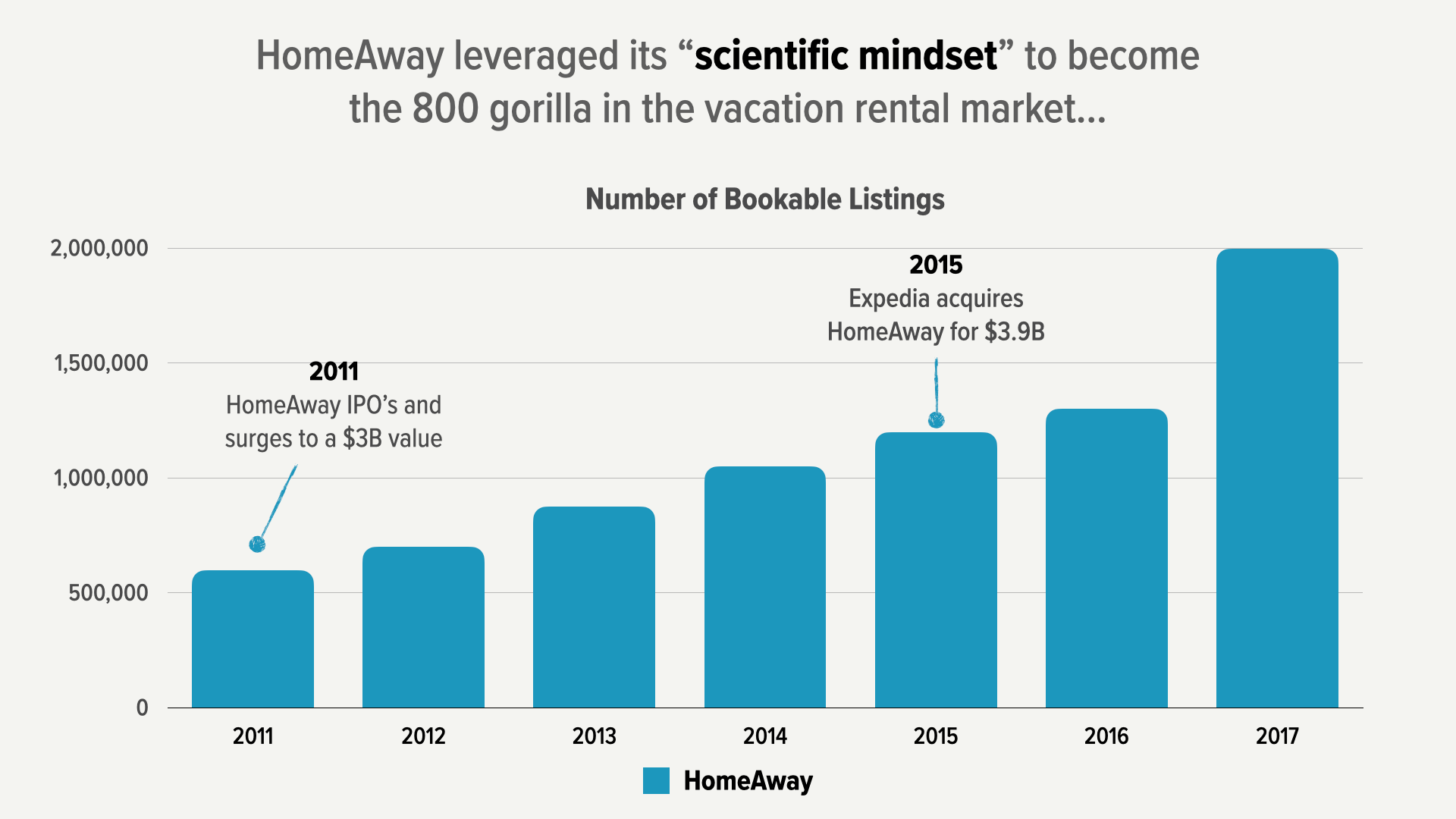

Launched in 2006, HomeAway (now part of Vrbo) has played a critical role in growing the vacation rentals market.

Like many travel companies, HomeAway excels at analytics-driven growth and optimization. The company cites a “scientific mindset” as the most important trait in new hires.

Since their IPO, they have delivered consistent 25-30% annual growth and generated about $1B in revenue (in 2018) for Expedia, HomeAway’s parent company.

In 2015, they were purchased by Expedia for $3.9B

This chart shows the growth in bookable listings on HomeAway, a key measure of success in the vacation rental market. It is a good example of HomeAway’s consistent, disciplined approach to growth.

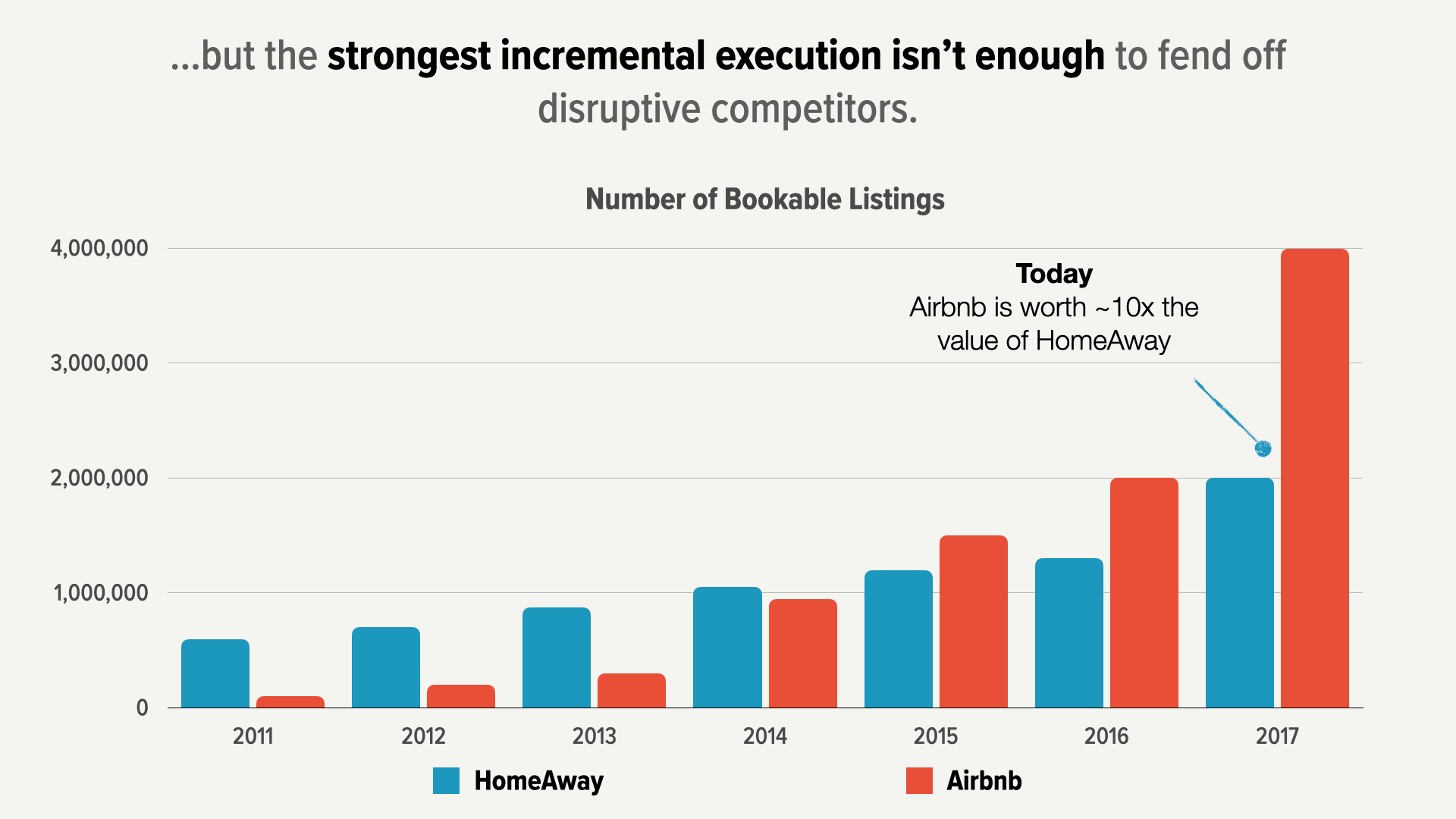

Airbnb has quickly eclipsed HomeAway, and the company is now the leader in the vacation rental market.

Like HomeAway, Airbnb is an analytical organization. However, Airbnb balances analytical decision-making with strong intuition and customer feedback.

Airbnb reframed vacation rentals as a transaction between two people: a host and a guest, rather than a business transaction between an entity and a customer.

As a result, they were able to develop insights that disrupted the market and accelerated their growth past the largest incumbent in the space.

In 2019, Airbnb was worth more than 10x the value of HomeAway.

Analytics is crucial to determining what is happening when people use a product, but it often falls short in explaining why. The “why” can make the difference between an incremental insight and a disruptive insight.

Customer feedback uncovers the “why” and is the equally critical third pillar in making good product decisions.

Decisions made using feedback are based on qualitative and quantitative research from existing and potential customers. This feedback can take the form of 1-on-1 user studies, focus groups, surveys, and independent market research & analysis.

At its best, feedback-based decision making fosters empathy and uncovers the heart of what customers want.

In the last several years, Silicon Valley has fetishized data-based decision making. There is no doubt that analytical decision making has played a critical role in scaling the most widely adopted products ever created.

At the same time, it’s important to remember that human behavior, needs, and wants are not so easy to quantify.

Airbnb is one of the best examples of a company that understands the distinction between what can be counted and what counts. They seek to balance analytically-driven product scaling with customer-driven product development.

Customer-driven product development is in Airbnb’s DNA. Early on, Brian and his co-founders spent as much time as possible with hosts and guests, often getting to know them as friends and staying with them.

We didn’t just meet our users, we lived with them. - Brian Chesky, CEO of Airbnb

In Masters of Scale, Reid Hoffman’s podcast about building startups, Brian Chesky talked about how he sees building a startup as two distinct activities: designing a magical experience for a handful of users and scaling the essence of that experience to hundreds of millions of users.

How do you design a magical experience?

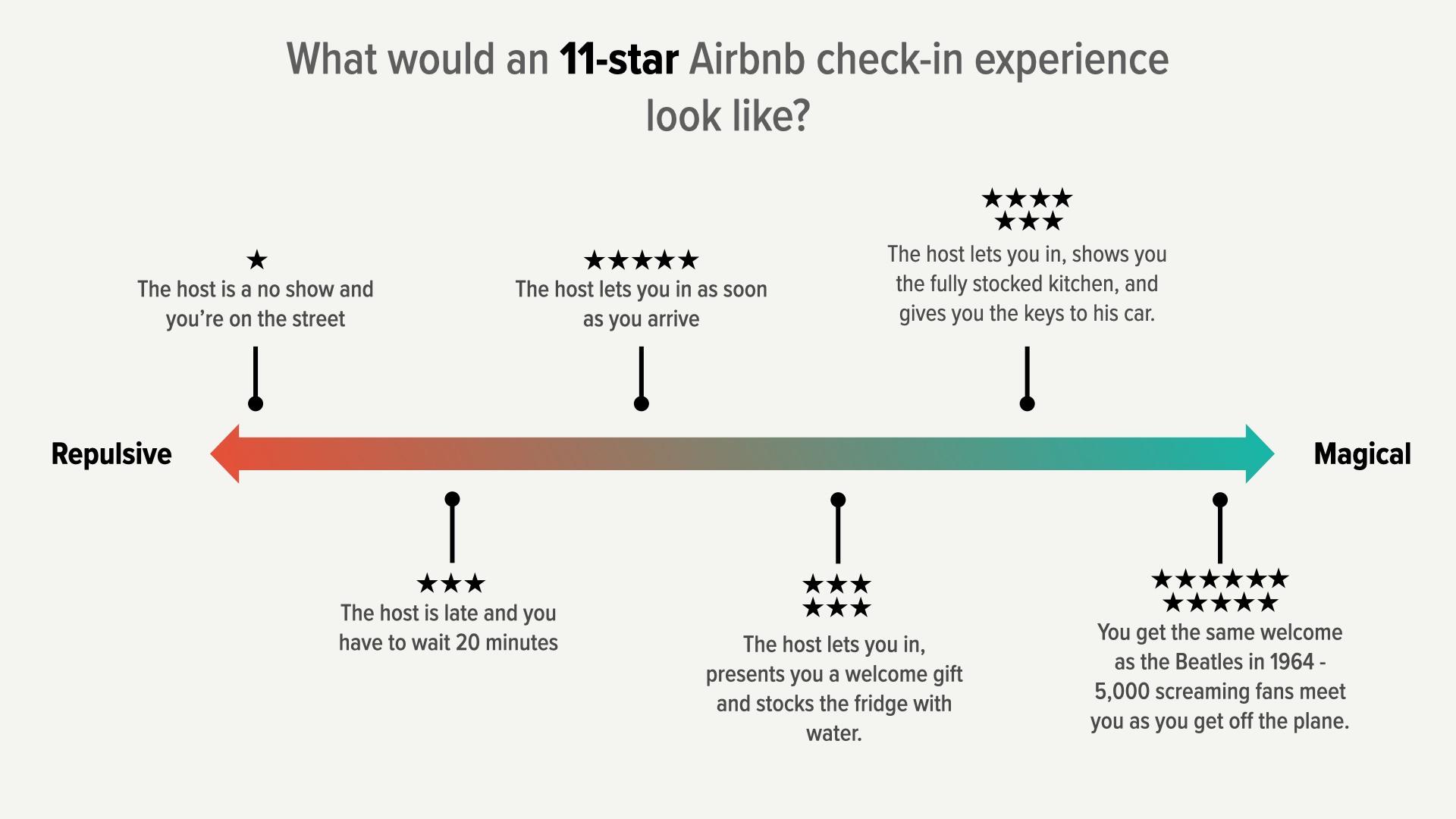

This starts by asking users not “What would make the product better?”, but “what would make you tell everyone in the world about it?” The goal is not just to define a 5-star experience, but to imagine an “11-star” experience and work backward from that to deliver something magical.

The 1-star experience for Airbnb check-in is not being able to get into your Airbnb. The 5 -tar experience is having the host let you in as soon as you arrive. That is where many companies stop, but extrapolating beyond “the best” is where the magic begins.

A 7 -tar experience begins with the host showing you around the place, grabbing a drink for you from the fully stocked kitchen, and offering to loan you the keys to her car.

The 11-star experience? Imagine how the Beatles landed in the United States. A red carpet and thousands of fans welcome you as you get off the airplane.

Sounds pretty fantastic, but is this practical? Let’s look at how Airbnb puts this brand of magical thinking into practice.

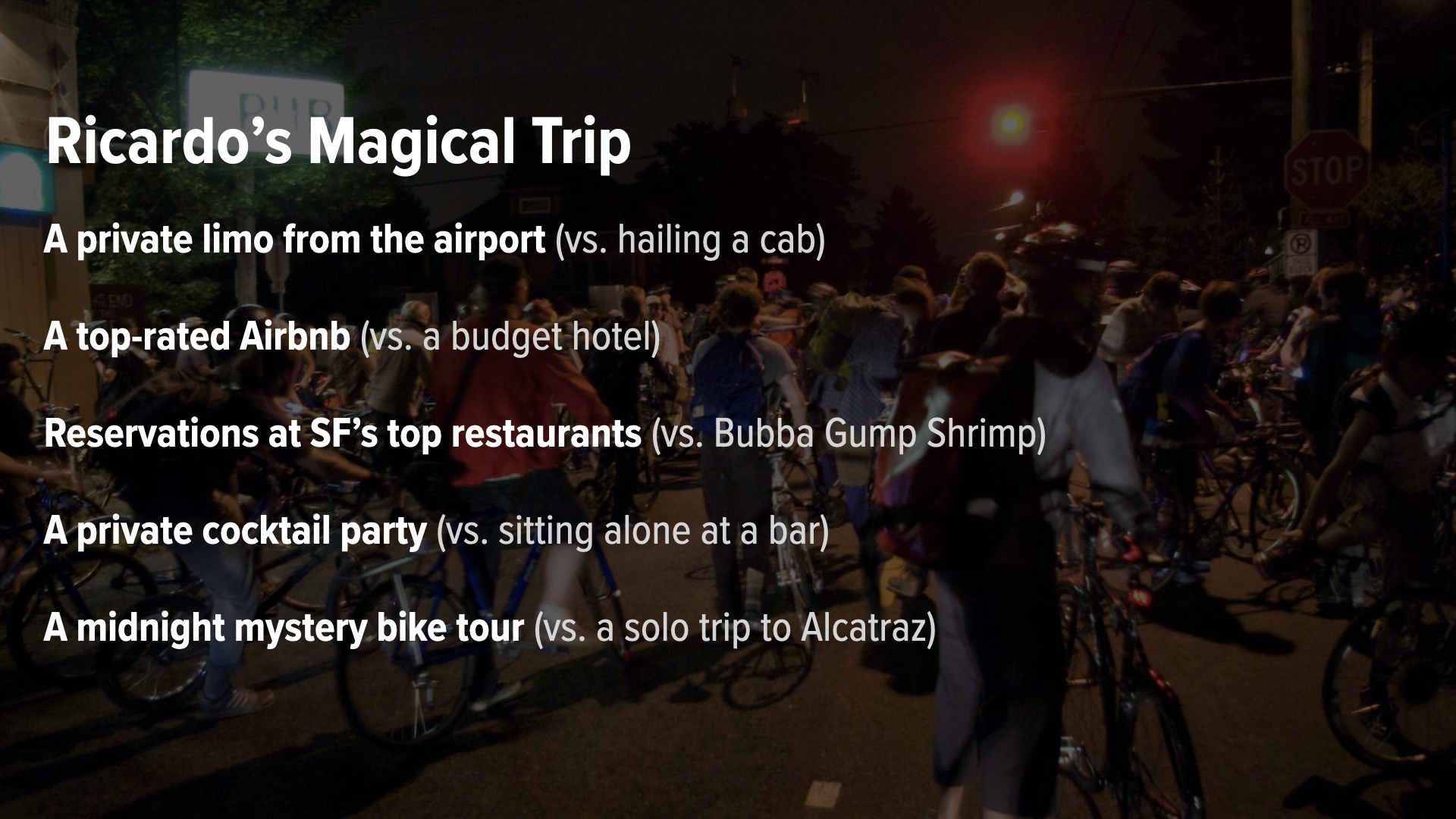

As Airbnb thought about moving beyond accommodations, the company wanted to discover what makes a magical trip.

They followed Ricardo, a traveler from London, on a solo trip he had planned to San Francisco. The trip was an unremarkable and sometimes lonely experience.

In fairy tale form, Airbnb offered to recreate the perfect trip for him. They worked with Hollywood screenwriters to storyboard the perfect trip with Ricardo cast as the hero.

Ricardo’s trip began with a private limo picking him up from the airport (no hailing a cab this time around). He stayed at a top-rated Airbnb rather than a budget hotel. The Airbnb team organized reservations at San Francisco’s top restaurants (on his first trip, the culinary highlight was a trip to Bubba Gump Shrimp Co.)

The trip culminated in a private cocktail party and a midnight mystery bike tour, an often overlooked, but top-rated attraction.

The trip was a moving experience for Ricardo. Overcome with emotion, he thanked the Airbnb team for several of the most memorable days of his life.

This is where the magic begins. Once Airbnb had crafted a deeply moving experience for a single traveler, they asked “how can we scale this to 100 million users”? Using this understanding, the team began working on Airbnb Trips.

Feedback is essential to understanding customers, but feedback must be used with judgement.

Poor use of feedback can lead to optimizing for the vocal minority, over-reacting to minor issues, and missing out on opportunities for innovating beyond what customers can describe.

At established companies, user research often takes significant time and resources. Smart PMs look for ways to plug into the customer conversations that are already happening. Often, these conversations will come from communities like Reddit and internal dogfooding.

Talking to customers is always useful. That said, the people talking about your product are the most heavily engaged and vocal. They may not represent the users who are in the most need of a better experience.

Several years ago, the OkCupid product team was spending a lot of time engaged with users on Reddit and using the product themselves.

These power users wanted to receive as many messages as possible. They had the willingness and ability to sift through a firehose of messages.

Analytics reinforced this perspective. On average, retention was correlated with message volume—the more messages received, the more likely a user was to come back.

This experience made sense for a small subset of power users, but overwhelmed new users, particularly women who received far too many messages on their first day.

The solution? Balance the vocal user feedback and the analytics with a dose of intuition.

Put yourself in the shoes of a new user. How many messages would you like to receive on your first day? Enough that you can begin getting value from the product by meeting new people, but not so many that the experience becomes overwhelming.

OkCupid reframed the feedback they were getting from users. More messages is not always better. The company took steps to improve the experience for new users by throttling the number of messages people could receive on the first day.

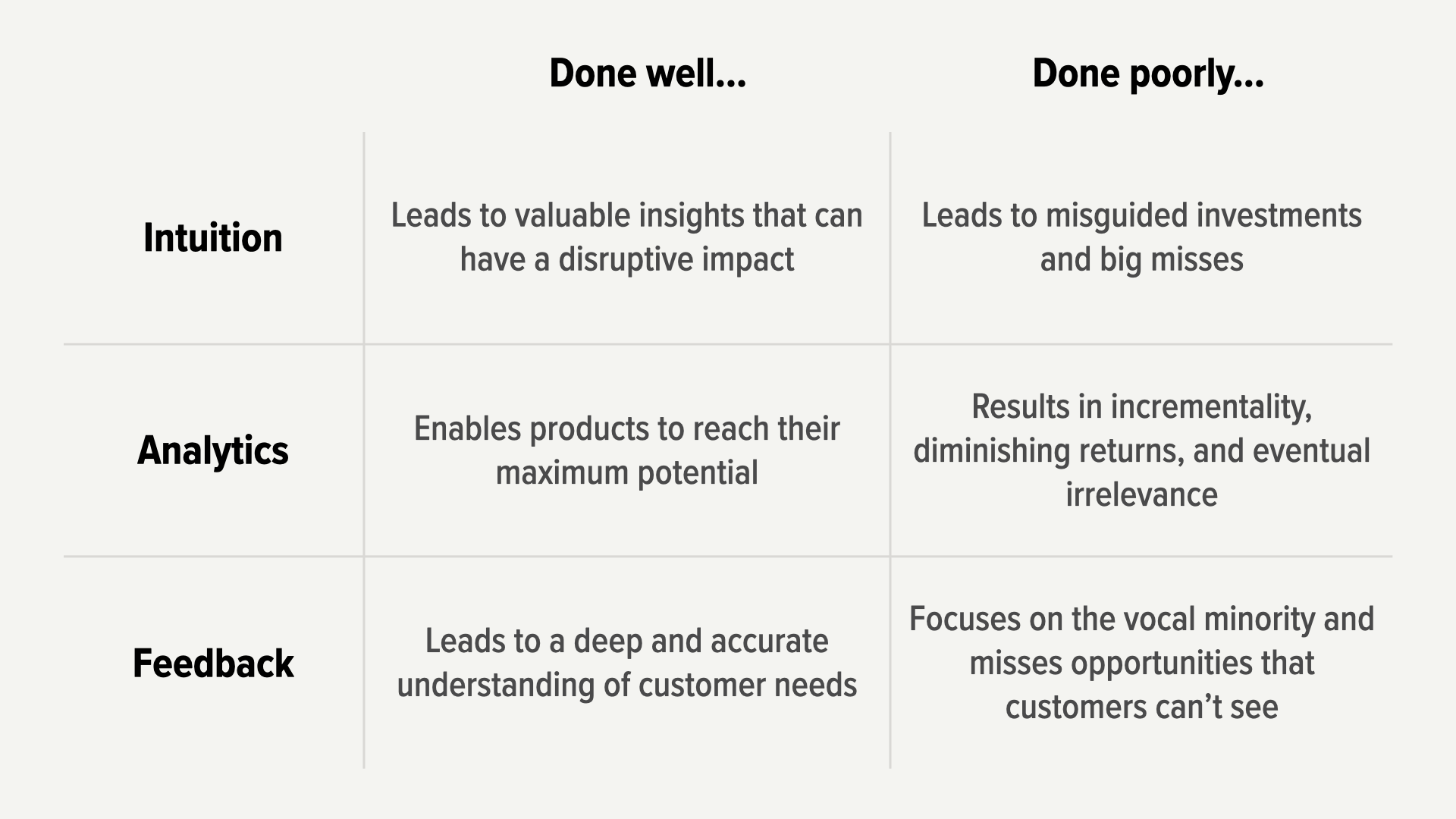

To review, there are three equally important pillars of product decision making: 1) intuition, 2) analytics, and 3) feedback.

Each has benefits and drawbacks:

- Intuition reveals valuable insights and quantum leaps, but may lead to misguided investments and big misses.

- Analytics enables products to reach their maximum potential, but may result in incremental thinking.

- Feedback leads to a deep understanding of the customer, but may put too much focus on a vocal minority and won’t uncover opportunities customers can’t describe.

The best decisions are made by striking a balance between intuition-based, analytics-based, and research-based decision making.

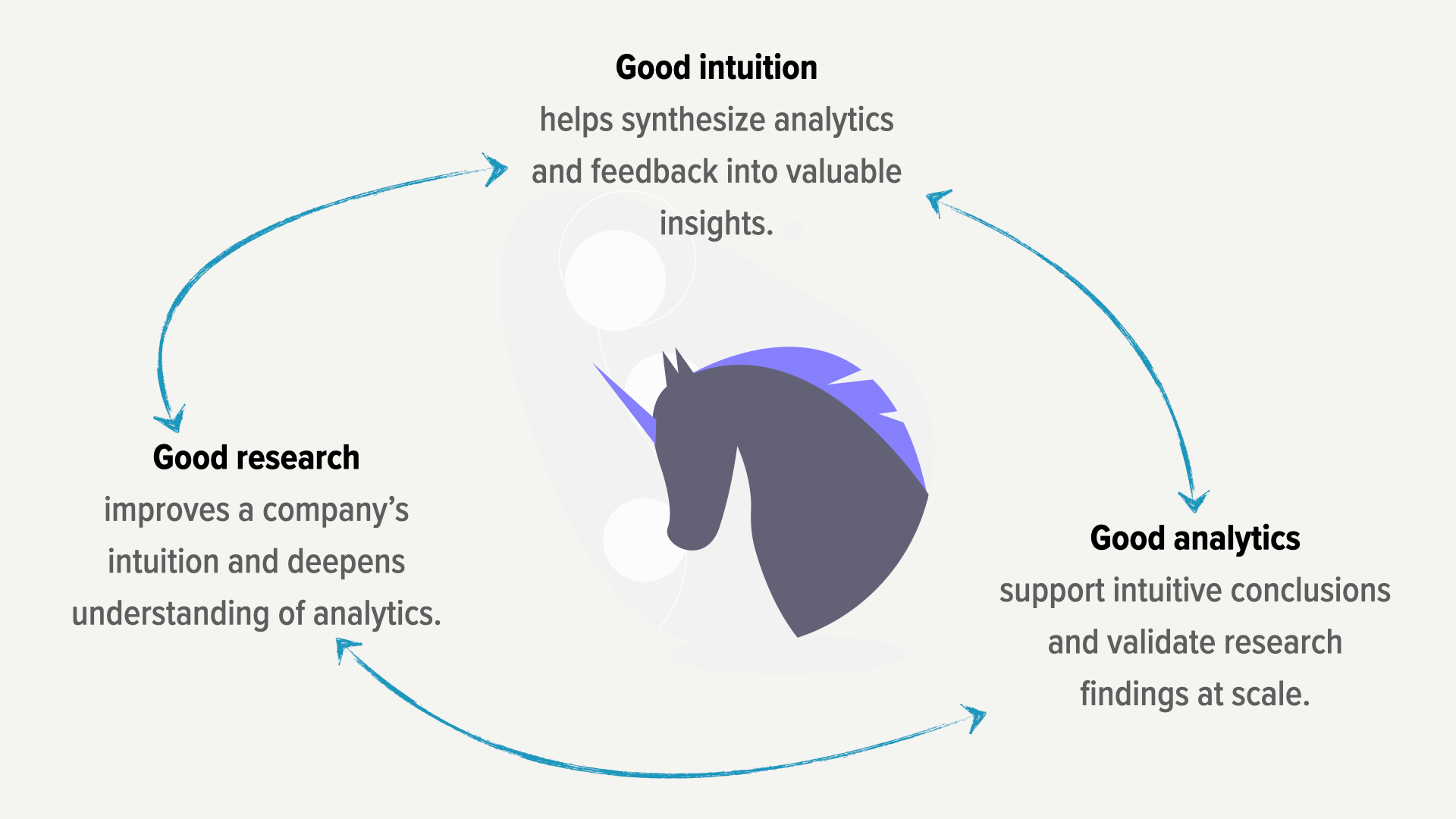

These approaches are self-reinforcing:

- Good research improves a company’s intuition and enables more actionable conclusions from analytics.

- Good analytics supports intuitive conclusions and validates research findings at scale.

- Good intuition synthesize analytics and feedback into a perspective that is greater than the some of the parts.

When done well, a balanced approach to product decision-making enables companies to 1) find product-market fit, 2) grow those successful products to their maximum potential, and 3) find new sources of product-market fit before they are disrupted by competitors.

Thank you to Gojek for inviting me to speak, and thank you for making it all the way through this epic read!

I try to answer as many questions as possible. Feel free to reach out to me on Twitter and LinkedIn.